China’s Ethnic and Cultural Diversity

Travel Along Yunnan’s Ancient Tea and Horse Caravan Road

Article and photos by Lies Ouwerkerk

Senior Contributing Editor

10/2014

|

|

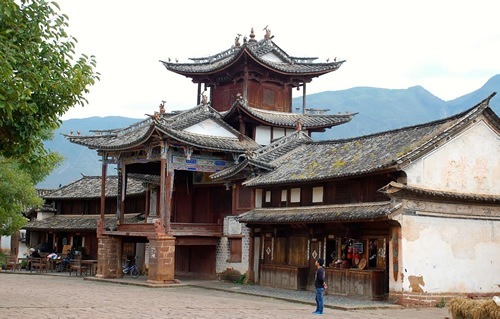

The ancient town of Shaxi along Yunnan.

|

China’s Ancient Tea and Horse Caravan Road was in fact not a single route but describes a complex network of trails. The trails were predominantly used for the exchange of tea, from the far southwest of China, for horses from the Tibetan plateaus in the north. The unpaved, rugged mountain paths ran from the southern provinces of Sichuan and Yunnan, along the foothills of the Hengduan Mountains, through the Three Parallel Rivers area and the Qinghai-Tibet Plateaus, to the Himalayas in India. Besides tea and horses, sugar, salt, herbal medicines, furs, musk, clothes, jewelry, and other fine local products were traded. The network dates back to the era of the Tang dynasty in the 7th century and was used for trade purposes until the mid-20th century when the Tibetan highways were constructed.

|

|

Drying corn and pepper: a common sight along the trails.

|

The trails were not used for trade alone, though. Buddhist monks would pass them to study and collect sacred texts in Burma and India, and Christian missionaries followed their footsteps into the most remote corners of southern China to spread the Gospel in the beginning of the 20th century. The revolutionary Red Army fled this way in the 1930’s, and during World War II, supplies were brought into China along these routes when Japan had blocked all other supply lines. And last but not least, the trails also served as a channel for communication among the large variety of ethnic groups inhabiting the southwestern provinces of China.

Currently, of the more than 46 million people living in the province of Yunnan, over 12 million belong to one branch or another of the more than 25 different ethnic minorities inhabiting the province, among them the Yi, Bai, Hani, Miao, Lisu, Wa, Naxi, Bulang, Yao, and Tibetans. This diverse cultural mosaic, coupled with magnificent sceneries — dense forests and rice terraces cascading down mountain slopes, remote villages and colorful markets in centuries-old trading towns, picturesque lakes and mighty river gorges, impressive glaciers, and over 4000 meter-high, snowcapped mountain tops — was a big draw for our small group of six travelers, eager to explore the lesser known areas of Yunnan in the company of our English speaking guide from Xixhuangbanna.

|

|

Lunch along the way.

|

|

|

Children assembling in a school yard..

|

Dai People

The villages we visit in Yunnan’s sub-tropic south, close to the Thai and Lao borders, are mainly populated by Dai people, making a good living off their rice fields, and the rubber and banana plantations in this fertile region. Labor of whole families is possible here: in spite of China’s one-child policy, all ethnic groups in China’s rural areas are allowed to have three or four children. Generally, when a son marries, he will stay in the parental home, and his wife will move in. If no son has been born, the oldest daughter will stay, and a son-in-law will be added to the family.

|

|

Women working in the fields.

|

The Dai (meaning: "free people"), a traditionally Thai ethnic group that migrated north, are extremely hospitable and often invite us into their houses to drink the famous Pu’er tea, or to admire their ceremonial attire, which they happily display in front of our cameras.

|

|

Aini woman with ceremonial headdress.

|

They don’t have surnames, as they were all part of one clan once upon a time. Males carry the prefix ai and females yu, and ancient noble families add the prefix dao.

Many Dai live in 2-story wooden houses built on stilts, with roofs adorned with paintings of peacocks, considered to bring good luck. On top of the roofs we often see little mirrors, which serve to chase away the devil, supposedly repulsed by its own image. Dai also attach empty bottles to their roofs, in the hope that bad ghosts will enter them and then get caught in the narrow necks. Although they predominantly adhere to Theravada Buddhist beliefs, centuries-old superstitions and animistic beliefs are obviously still pervasive.

|

|

Dai house with peacock.

|

Hani People

Close to the border with Vietnam, we admire the spectacular Hongha Hani rice terraces, filled with water all year round, which cascade down the slopes of the verdant Ailao Mountains to the banks of the Hong River. Over many centuries, the Hani (and to a lesser extent the Dai and Yi), inhabitants of this area, have developed a sophisticated system of channels through which water from the mountaintops is brought to the rice terraces on the slopes and in the various valleys below. Their origin is not exactly known, but they are believed to have migrated from the north, possibly the Tibetan plateau. At the local market in Yuanyang, we meet various minority women selling products from their land, all proudly wearing their traditional clothes in very colorful, elaborately embroidered patterns.

|

|

The Hani rice terraces around Yuanyang are testimony of an awe-inspiring centuries-old rice cultivation.

|

Wa People

We make a detour to visit Wengding, a remote village of about 100 households belonging to the Wa group, traditionally a tribe of ferocious jungle warriors and headhunters (until a few decades ago), and one of the best preserved ancient communities in China today. Like the Hani, the Wa practice ancestor worship, and believe that everything is determined by spirits housing in water, trees, and mountains.

At the entrance, next to a huge totem pole and piles of ox skulls — regarded as a symbol of fortune and power — we are welcomed by villagers playing bronze drums and donning our foreheads with a firm dot of black paint.

Wandering through the little lanes lined with thatched roofed bamboo houses, and passing black-robed, pipe-smoking women on their way to the fields, we suddenly bump into a large gathering of people sitting outside one of the houses, chatting, laughing, and drinking. They explain they are guests at a baptism ceremony that is taking place inside, and gesture to us to enter the house.

|

|

Wa woman smoking a pipe.

|

We climb up the stairs to the living quarters (the open lower part of the house serves as space for livestock and keeping pest at bay), where groups of men are seated on the floor, a committee of older men in one corner, and a circle of younger men cutting meat and dividing it over loot bags in another. One of the village elders receives presents and money from the guests, hands the gifts over to the young parents, and then breaks into a chant while holding a lit torch above the head of the mother with the baby in her arms. Once the ritual is over, the party can begin and rice wine flows...

One of the villagers takes us to a sacred forest outside the village, where the dead are put to rest in spaces indicated by a religious expert, called the moba. They are buried in coffins made from hollow trees, split in the middle. Once the burial has taken place, the site is fenced off with bamboo screens and ox skulls, to keep away scavenging animals and evil spirits.

Elsewhere in the village we are invited into the modest home of a farmer’s family, to sample various kinds of tea, brewed on a little fire on the floor. Before serving us, the farmer first dips a finger in his own cup and sprinkles the floor with the liquid, for good luck. Then he lifts the whole coffee table, out of respect for his guests, and offers each of us a cup. He is obviously distraught about the recent plans of the Chinese government to uproot all villagers to new stone dwellings outside the ancient village, in order to turn the original bamboo structures into a commercial tourist project. They will have to pay half of the new house, which is still a hefty price for them. But more importantly, his current home is perfectly situated under the trees, between the river below, and the mountains up high. The newly assigned dwelling, however, lacks this fortunate natural alignment, and he firmly believes that this can only bring his family bad luck.

|

|

Wa woman.

|

Naxi, Yi, and Bai People

Some famous old towns and villages, once mayor cross points and markets along the Ancient Tea and Horse Caravan Road such as Dali and Lijiang, have been listed as cultural heritage sites by UNESCO, and this has unfortunately resulted in the recent development of a booming tourist industry. Today, the beautifully restored ancient wooden houses of these towns are turned into souvenir shops, café’s, restaurants, and tourist agencies, and the picturesque narrow cobbled streets and bridges are now treaded by the feet of hordes of tourists instead of horse caravans.

|

|

Yi woman with black head dress.

|

It comes as a total shock to us, after having traveled through the peaceful remote villages of the far south, but luckily we still find ways to meet with the authentic Naxi, the main ethnic minority in this area: at markets hidden behind the main arteries where they trade their homegrown vegetables, in parks where elders play cards and mahjong, and outside town where they labor in their fields or build new houses in their little villages.

|

|

Bai women on their way to a funeral.

|

Also, there are several ancient towns between Lijiang and Dali, which are beautifully preserved but much less visited, such as Weishan and Shaxi. A bike ride through the surrounding countryside presents ample opportunities to meet with hospitable Naxi, Yi, and Bai, and drink tea at their farmhouses adorned with drying peppers and corn.

|

|

Naxi woman with child.

|

Tibetan People

Past spectacular natural wonders like the famous Tiger Leaping Gorge, the limestone terraces at Bashuitai, the “Curve of the Yangtze River" and the Haba Snow Mountains, we reach the once cut-off town of Zhongdian — nowadays called Shang-gri-la, and named after the mythical Himalayan paradise in James Hilton’s novel Lost Horizon. Zhongdian, where Tibetans have been the dominant ethnic group for several centuries, now attracts tourists by the millions as a consequence. The local government, aware of Tibetan culture as tourism’s main draw card, provided the formidable Zhongdian’s Songtsam in Monastery with a huge grant to renovate its buildings, as soon as the close-by Diqing airport was opened in 1999.

|

|

Songzanlin Monastery, Shangri-la.

|

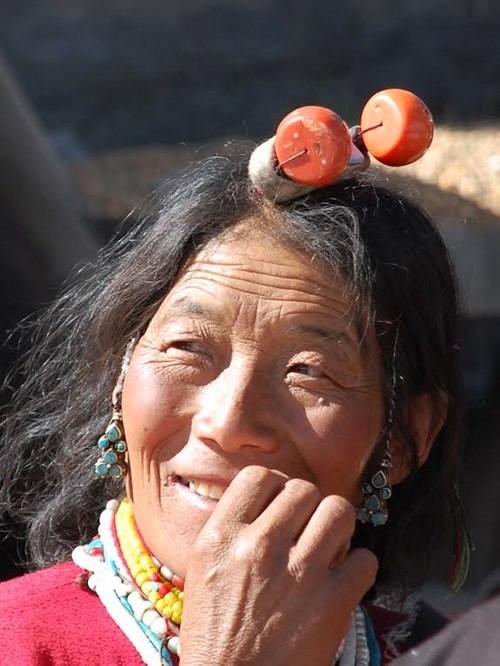

At the much lesser known, but equally impressive Dondrupling Monastery, close to the traditional Tibetan village of Benzhilan, we hit the jackpot: not only are we able to attend a ceremony in one of the temples, but we also witness the monks’ dance and music practices in a courtyard at their nearby living quarters. And in the village of Nixi, nestled in a misty green valley by the Yangtze River, an employee of our hotel introduces us to villagers living in white stone Tibetan farmhouses, and to painting and black pottery workshops where the same complex techniques are used as thousands of years ago.

|

|

Dondrupling Monastery monks practicing for an upcoming ceremony.

|

|

|

Tibetan woman.

|

Letting ourselves be pampered at the end of our pilgrimage in one of the five exquisite Songtsam lodges, all constructed a hop, skip and jump away from daily village life in spectacular natural settings, decorated in authentic Tibetan style, run with much care by people from the area, and offering meals prepared with only locally grown produce, cannot be a better ending to a fascinating trip among so many diverse communities along the Ancient Tea and Horse Caravan Road.

Lies Ouwerkerk is originally from Amsterdam, The Netherlands, and currently lives in Montreal, Canada. Previously a columnist for The Sherbrooke Record, she is presently a freelance writer and photographer for various travel magazines.

|