Food Markets in Rabat, Morocco

By Beebe Bahrami, Ph.D.

|

|

Medieval Rabat from the port.

|

Lunchtime was still a good two hours away. Regardless, the old city center, Rabat’s fortress-walled medina built in the 12th century and then rebuilt and expanded in the 17th century, was filled with midday shoppers and the smells of fragrant spices, including cumin, paprika, coriander, cilantro, briny preserved lemon, garlic, onions, saffron, and olives. Someone in this maze made a chicken and olive tajine, that complex, rich, fresh, and spicy terracotta vessel-baked stew for which Morocco is famous.

This was a daily conundrum during the year I lived in Rabat: No matter how satiated I was before going food shopping, I always became exceedingly hungry once I entered the medina. It was a hunger brought on by so much good food, be it the daily market offerings or the master chefs in their private quarters above or behind the kiosks preparing lunch or dinner for their families and enveloping the medina with magical aromas.

Food indicates the supreme importance of family and friends in Morocco, and people will take time to prepare it and eat it with others. Slow Food, Buy Local, and Buy Fresh are the rule, not the exception.

Exploring the Heart of Rabat's Medina

When you enter one of the Rabat medina's several stone-arched gates off of Hassan II Boulevard and step to your left or right, taking one of the few central streets, your senses are engaged: it is an intense, colorful, fragrant-rich, succulent, and immensely gregarious place to be. To your right or left might be the women selling flatbreads and crumpet-like pancakes. The women are dressed in their crème or mushroom-colored jellabas hooded robes. Some have hennaed hands, indicating they may have recently attended a relative's or friend's wedding. Their breakfast goods and bread are stacked like a money counter's coins on small tables before them. Behind them, the old wall and trees around a tiny shrine offer shade and calm.

Deeper in the maze-like streets of the medina are the fruit and vegetable sellers. Some are in orderly kiosks; others sell produce on oilskin cloths on the ground, but all offer only fruits and vegetables that were just harvested and local — baby artichokes, carrots, zucchini, okra, green beans, tomatoes, buttery green lettuce, and endive among many other seasonal choices. In the morning, some fishermen have just hauled in their coastal catch and are setting up scales on the path to swiftly get the fresh fish into capable hands.

Morocco is a land of varied landscapes, with two coastlines, one Atlantic and the other Mediterranean, four mountain ranges, valleys and plains in between, and finally, the desert at the country's southern end. This rich diversity guarantees a bountiful and varied local diet. Rabat's coastal climate feels like that of southern California, while its growing seasons are more like northern California's due to rain throughout the year.

Amidst all this, women shoppers rub elbows, vying for the best produce and bargaining. As they walk past or negotiate for room at a kiosk counter, their long jellabas shimmer with their myriad jewel-toned colors of emerald, fuchsia, orange, scarlet, violet, lapis, and lemon.

Despite their mothers' fierce verbal skills and poker faces, the children of the women shoppers cast mischievous glances and big, glowing, curious eyes at the rich, dynamic, textured, colorful, and time-honored market world around them.

Aromatic Encounters in Rabat: Spices and Tajines

|

|

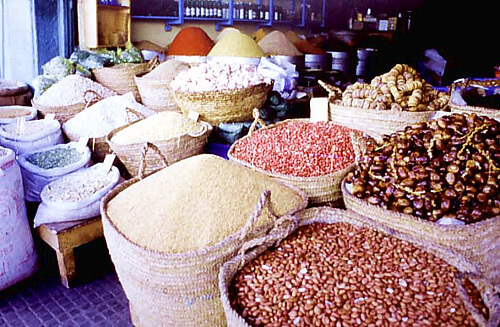

Food and spice market in Rabat. Photo

courtesy of Adrienne Alvord.

|

Further down, there are the butchers. One waits for his next customer, leaning forward with his elbows resting on a stack of sheep and cows' feet cut at their elbow joint. His head fits between the hanging display of kidneys and livers on one side and tripe on the other. Beyond him are older men, in their wooly brown jellabas and white skull caps, shuffling through, looking at each display. One stops at a spice stall, taking in the sand dune mounds of paprika, cumin, coriander, curry, turmeric, fennel, cardamom, caraway, and saffron.

Not far away is an older man; he must be as old as a medieval wizard and looks just like one with his long white beard, golden silk turban, and sparkling blue eyes. He sells dried rose buds, ground henna, terracotta skin scrubbers for the bath, loofa sponges, herbs, and amulets to cure, protect, and procure the user's wishes. If you stop and tell him your concerns, he will advise you on the proper herbal mix. (He often sold me beautiful tiny rose buds, which I used in cooking and making foot baths smell good. Each time I saw him, he would teach me Moroccan Arabic, laughing kindly at my efforts to drop as many vowels as possible, a distinguishing aspect of Moroccan Arabic. Also, Berber is a native language and very widely spoken, as is French, followed by Spanish, Italian, German, and many other languages: Moroccans are incredibly multilingual, reflecting their geographical place at the crossroads of human history.)

The medina is a medieval walled-in city within the larger city of Rabat, as is the case with medinas in other parts of Morocco. It has indoor and outdoor caverns, a few main thoroughfares, and infinite capillaries that shift as regularly as the daylight and shadow across the narrow passages. Further, beyond the food markets, lay carpets, ceramics, woodwork, jewelry, clothing, music recordings, and much more — much of this is along Rue Souika, which is the main street you will encounter upon entering any gate from Boulevard Hassan II, and on to the other main street in the medina, the Rue des Consuls. Two peripheral areas at each end of the medina also boast remarkable flea markets offering purely Moroccan treasures amidst lots of second-hand junk and pieces from the colonial era.

If you walk through the medina toward the ocean side, you will come upon a stretch with a view out over the ocean. You can cross the main road, Rampe Sidi Maklouf (carefully), toward the fortress, the Kasbah des Oudayas, and explore this small walled neighborhood overlooking the river and the ocean.

Within the Oudaya is a lovely Andalusian Garden, a recreated remnant of the 17th-century occupants. These moriscos arrived here as exiles from Spain around 1609 and made the fortress and the medina below their new home. The moriscos made Rabat an independent pirate republic for the first half of the 17th century. In the Oudaya, you will see indications of this, the most pronounced being the canon at the highest point, which points in three directions: across the river at Sale, up the river, and out over the ocean. They were fiercely independent before the Moroccan Sultanate absorbed the Iberian refugees in 1666. This meant they were at odds with the folks in Sale (one canon), with anyone coming downriver (a second canon), and filtering who they let in or out from the ocean-river mouth passage into their harbor (the third canon). In the Oudaya, you will also find their 17th-century palace, a fine example of late Muslim-Christian-Jewish Iberian styles brought back to Morocco and fused with local aesthetics.

The medina everywhere in Morocco (every town and city has one, and every village has a market square) is alive, with people there to buy their daily food. Many still do not rely on refrigeration or the concept it represents, less than day-fresh food. The medina also has its own neighborhood in Rabat; many people live in its numerous labyrinthine back streets that wind away from the shopping area.

From Farm to Table in Morocco: Fresh Produce and Seafood

The beauty of traditional food shopping in Morocco is that you buy it every day, fresh, locally, seasonally, and from your neighbor who is also cooking a killer tajine, better than anything you'll ever eat in a restaurant. Home cooks are the masters, and chefs study with them if they are wise. This is not to cast aspersions upon restaurants — some stellar ones are worth visiting — but nothing compares to what is bubbling away in a home kitchen.

A drive in the surrounding country reinforces these realities as one witnesses the activities of people who still know how to grow local, seasonal, and healthy food. A typical scene is a woman churning butter in a heavy linen sack that is suspended between two poles with her rocking it back and forth; a man and a donkey pulling a cart with baskets full of flower blossoms ready to go to market to sell for making flower water; cherry pickers selling just-picked ripe ruby red globes or white truffle sellers advertising pyramid-piled truffles on upturned 10-gallon cans on the roadside. Beyond them are sweeping fields of spring green and cadmium red poppies.

Recommended culinary souvenirs are saffron and ceramics. If you love authentic cooking tools, select a terracotta tajine dish to carry home. Ceramics are a diverse undertaking; each city and region produces distinctive styles of shapes, colors, and painting designs. As for saffron, it is grown in southern Morocco, around Taliouine, south of Marrakech, and available in almost any marketplace. Some consider Moroccan saffron of a lesser quality than Spanish or Iranian varieties. Still, I advocate for terroir in all its manifestations. You can taste the unique mineral-plant composition of Moroccan earth in Moroccan saffron. This holds true for the red wines produced in the Fez-Meknes valley (Amazir is my favorite), and those extraordinary white truffles sold roadside in spring in central Morocco.

There are also some little treasures for food shopping outside the medina. The petit marché is on Place Pietri in the heart of the more modern city. Its architecture speaks of its colonial French occupants and more contemporary structures associated with an independent Morocco. Here, you will see the flower market, le marché aux fleurs, in riotous color year round and with flower vendors and flowers of every imaginable variety, African, Asian, and European. Steps leading to an airy underground space take you to the little covered food market that boasts a good butcher, cheese sellers, a sausage vendor, herbalists, and specialty foods imported from France.

Every neighborhood has several bread bakeries and pastry shops, staples of the daily diet. Just follow your nose and eyes. Most bakeries are excellent and excel in Moroccan breads (whole grain flatbreads being my favorite) with French breads (baguettes being as good as in France).

Each neighborhood has a fruit and vegetable seller throughout the city who might have a little kiosk along a high stone wall or in a row with other small specialty shops. On the roadside, you might also see someone with their coal fire and vat of oil making puffy fresh fried donuts. Another roadside merchant might have coals on which he is roasting corn. Toasted nuts are another street snack specialty.

A Glimpse into Traditional Moroccan Crafts and Ceramics

|

|

Markets in Rabat selling traditional crafts.

|

Just below the Oudaya is a craft center where ceramics, leather goods, wood crafts, and more are sold. Moreover, further up the river in the Rabat-Sale river valley is a potter's guild where artisans gather in shops and buildings like a small village in and of itself. This is a fine place to buy locally made ceramics, baskets of all shapes and sizes, jewelry, and other artisanal goods.

The Tradition of Slow Food in Moroccan Culture

This perspective on local, seasonal Slow Foods might seem challenged by the presence of superstores in Rabat. But one of my fond memories of food shopping in Morocco was visiting the hypermarché (supermarket) Marjane, ironically, in Rabat and Sale's river valley, the region's traditional farmland that produces much of the local vegetables and fruits. I was worried about what this mega store would do to the incredible selection of locally grown and sold seasonal foods. I entered the store behind a Moroccan family who, like me, were there to take in the new phenomenon. Parents, children, grandparents, an aunt and uncle, and a cousin moved through the store as a unified group the way tours go through museums. They went from product to product, display to display, and fruit and vegetable to fruit and vegetable. They would not be rushed even though they were in a convenient and fast hypermarket. If the food did not meet their standards of freshness and taste — they picked items up, felt them, smelled them, eyed them closely — they would resume their old ways of shopping from local greengrocers and fishmongers and butchers (this I overheard them say to each other as I followed in their wake).

Subsequent trips to Marjane taught me that ease and convenience in Morocco will only go as far as quality and taste meet traditional standards. In other words, Moroccans are lovers of food with very high standards.

Beebe Bahrami is a freelance writer and cultural anthropologist specializing

in travel, food and wine, and cross-cultural writing.

|