Inside the Monk's Cave

Parting from Thailand

Article and photos by Paul King

|

|

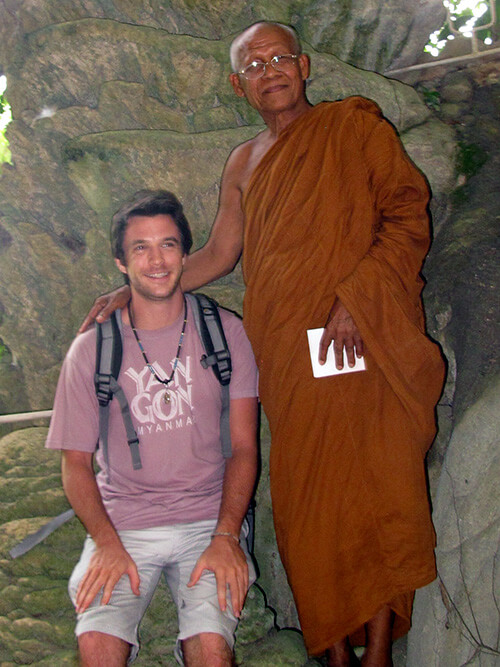

Monk inside the cave.

|

I take a sip from my cold Singha Beer glass and listen to the band. Yui sits on a stool before the drummer, wearing high heels and a tight jean skirt. Like many Thai women, she is thin and attractive, with straight, long hair. Underneath the orange and yellow lights of the stage, her bronze-olive skin seems to shine. She holds the microphone gently in front of her lips as she sings softly over the strum and rhythm of the acoustic guitar. As I listen, I manage to catch some of the words.

“Khru Paul,” says a voice. I look over, and it is Mon. Her hair is short and crew-cut, with the tips bleached blond, and she is holding a fresh pitcher of Singha.

"Will you come out with us to Say Yes tonight?” she says, smiling. “We’re all going when we get off work.”

Behind her, the guitarist drops into his solo, and the drummer crashes down on the cymbals. Mon leans in to whisper to me over the music.

“Yui will be there,” she says.

“Oh?”

“Ka,” she says, pouring more beer into my glass. “She told me backstage that she hopes you’ll come.”

“She said that?”

“Think about it,” she says, pushing my full glass towards me before she slips off into the crowd.

As I'm about to take another sip, I feel a hand on my shoulder.

“Nong Paul,” says a voice. I know who it is immediately — only one person in this town refers to me as Little Brother.

“Hey Pee Sid,” I say, employing the familiar family term. As he sits down, I can smell the whiskey on his breath.

“I thought I’d find you here,” he says. “I came to get you. My wife’s not around tonight, so I’m getting drunk and singing karaoke. Come on — everyone’s waiting. We want you to sing "Country Roads." You’ve got such a nice voice — it really is exactly like John Denver. No, wait, not that one…How about "Imagine?" You can sing that, can’t you?”

Before I can respond, Sid grips my shoulder and begins rocking back and forth, singing poorly intoned English: “Ee-mah-jin onn duh pee-punnnn…”

My phone rings, and I pull it out of my pocket. While I don’t feel much like answering it, I glance at the screen and see that it’s Jaemsri. Suddenly, I feel, as I always do, a sudden imperative. My surrogate Thai mother – retired English teacher extraordinaire and well-renowned judge throughout the entire south of Thailand — has something about her that grabs and demands one’s attention. She has that effect, whether with me, her former students, or even the mayor of Trang himself.

I flip open the phone.

“Hi Mom,” I say.

“Paul,” she says, getting straight to the point as usual. “You need to come home right now. The monk is coming.”

“What?”

“The monk,” she says, " the one I told you about, from the cave. Please come and make merit with Dad and me. You are leaving soon to go home to America, and you need to have his blessing.”

As usual, she hangs up before I even have a chance to argue.

I look at Yui up on stage and feel a pang of regret. Then I turn to Sid.

“I’m sorry,” I say to him. “I can’t tonight.”

He looks crestfallen. But as I push my nearly full glass of beer towards him, his face softens slightly.

“Okay,” he says, taking the glass in his hand. “Tomorrow night.”

I nod. Then, I get up from the bar and make my way out into the darkness.

* * *

When I pull into Jaemsri’s driveway, she, her husband (my “Dad”) Cherdchai, and a few neighbors sit on chairs and sofas around the veranda. An older-looking monk in orange robes, with spectacles and a shaved head, sits on the largest sofa against the side of the house.

“Paul,” says Jaemsri. “You’re just in time. Come and have a seat.”

As I approach the monk, I pay my respects in Thai fashion with a deep and formal wai. Getting down on my knees, I place my hands and palms against my forehead. Then, I lean over in a low bow, putting my forehead and both hands facedown against the ground. I come back up on my knees and repeat the wai twice more.

“Keng, keng!” says one of the neighbors, clearly impressed. As I get up and move to sit next to Jaemsri, she is beaming.

“This is my son,” she says to the group, full of pride. “Just like a Thai man.”

“Has he got a girlfriend yet?” says another of the neighbors.

“No, and he’s leaving soon to go back to America. He’s going to make every girl in Trang cry.”

At this, everyone laughs, including the monk. It’s a rich, authentic laugh, and his eyes shine.

“He will go back to America?” says the first neighbor.

“Yes,” says Jaemsri. He will return in one week after almost two years with us.”

“And what will he do when he goes home?”

“He’s going to write a book!” says Jaemsri, smiling widely. The monk eyes me curiously before turning and saying something to Jaemsri. As he speaks, her eyes light up. Then she turns to me.

“Did you understand what he said?” she tells me in English.

“I’m not sure,” I say. The monk speaks Thai quickly and uses the regional dialect of the south, which is difficult for my Bangkok-trained ears to catch.

“He has invited you to stay with him at his cave,” she says. “You must go. On your way to Bangkok. You will make a lot of merit.”

Before I have a chance to respond, she turns to the monk.

“He would love to come stay,” she says to him.

I swallow, and the monk looks at me and smiles.

* * *

The monk’s cave is in Phang-nga, a province about two hundred kilometers north of Trang. Dad drives Mom and me up Highway 4, the main artery up the western Andaman Coast. Outside the window, I watch endless groves of rubber trees pass by. Glimmers of sunlight pass through the leaves, falling like dust on the hood and windshield of the car.

When we turn off the highway, we ascend among rolling green hills. Up above, the sky is a brilliant blue, with only a few wisps of clouds. Outside, we pass a slowly moving motorbike, hitched to a wooden sidecar carrying two large propane tanks. The driver’s face is burned dark from the sun, and a small bamboo cheroot hangs between his lips, its tip glowing red against the dark mahogany of his skin. Other than him, there is no other traffic on the road.

We turn onto a dirt track, and as the car rumbles among the pebbles and dust, I see a large sign ahead with the headline, By Royal Decree of His Majesty the King. Underneath is a lot of small, fine print that I cannot catch. The dirt track dips and curves further until we see a large limestone cliff looming ahead.

“This is it,” says Jaemsri.

Cherdchai parks the car in a small, grassy clearing at the foot of the cliff.

About twenty yards away, cut into the rock, a staircase climbs its way upward.

As we leave the car, the monk appears, seemingly out of nowhere, holding a broom and smiling. Peering out from behind him is a small boy, perhaps about nine or ten, with a shaved head and wearing his orange robes. He is a naen, or a novice — a young boy who lives at the temple for a traditional period to learn the ways of monkhood. He eyes me curiously as I hoist my backpack onto my shoulders.

“Well,” says Jaemsri, and I turn to her. Tears are in her eyes, and she leans in to embrace me.

“We will always love you like a son,” she says. “Come back and stay with Dad and I anytime.”

“Thank you,” I say, tears welling up, " for everything you’ve done for me.”

I kiss her on the forehead and turn to Cherdchai. He smiles and puts out his hand. I take it and lean in to hug him.

“Okay, okay,” he says, laughing and patting me on the back. Then, in English, he says, “See you again.”

They get back into their car, and I watch as they pull out of the drive, dirt, and dust flying up in a cloud behind their black four-door. Like most Thais I’ve met, they are not big on goodbyes. Perhaps there is no such thing as a goodbye in a culture where reincarnation and repeatedly meeting one another across lifetimes is an underlying belief.

I turn around to face the monk, who stands staring at me.

“Teacher,” whispers the little boy to him, pulling lightly on his robe. Where’s big brother going to sleep?”

Big brother? The monk grins widely.

* * *

The monk has living quarters in a small house at the foot of the cliff. He invites us inside, where he has prepared a wok full of steaming pad see iw noodles. He says nothing, but his smile lets us know the meal is for us. I thank him, and the boy and I help ourselves. After we finish, I wash the dishes and put them on the drying rack next to the sink. Then I turn and face the monk, who stands sweeping his small living area. He smiles again and says something to the boy in rapid-fire southern Thai.

“Okay,” says the boy, pointing outside. “We go up.”

I look at the monk, who nods and returns to sweeping.

We make our way back outside, and the boy runs on ahead. I roll my suitcase across the grass and dirt to the foot of the staircase and look up. The stairs go up the cliff as far as I can see before they turn a corner and continue. With my large backpack on my back, I move forward, hoisting my suitcase up one stair at a time.

When I reach the first landing, the little boy is standing there and smiling.

“Nueai yang?” he asks. Tired yet?

“Yes,” I say, leaning my weight against my suitcase and wiping sweat from my brow. “Is it much farther to the top?”

“No,” he says. Then he sprints up the stairs as if to taunt me.

I continue the rest of the way, grunting and sweating, until we reach the cave's wide mouth.

“Take your shoes off here,” says the boy, kicking off his sandals before entering. I do the same and follow him.

When I step inside, my bare feet sink into something soft and smooth. When I look down, clean, white sand coats the ground.

“The monk brought it up from the sea,” says the boy simply, twisting his toes into the fine grains before leading onward.

The cave is high and wide and lit with electric bulbs along the ceiling. Soon, though, as we twist and curve our way further back, the bulbs disappear, and the only light comes from the flickering of candles up ahead. The boy moves towards the light, and I follow.

We step into a room with a small raised altar. Sitting upon it, along with burning candles and joss sticks, is an image of a reu-see — an old hermit or anchorite, unique to Thai legend. Seated in a meditation posture, with his long white beard and gentle eyes, he looks serene and full of wisdom. In front of him sits a small canvas tent pitched upon the sand. The boy unzips the flap door and motions for me to put my bags inside.

“You’ll sleep here,” he says. “There’s a bathroom back near the entrance, if you need to use it.”

I nod and put down my bags. After the boy scampers off, I strip out of my clothes — keeping the tent between me and the prying eyes of the hermit — and put a towel around my waist. Grabbing a bar of soap and shampoo, I head back through the cave to a small bathroom in a natural opening in the rock. As expected, the shower is just a large barrel of cold water with a pail. I dump some water on myself, lathering, rinsing, and feeling the chill of the water against my skin. When I made my way back, the little boy had returned and was lying inside the tent.

“What are you doing?” I ask, pulling a pair of shorts on underneath my towel.

“I’m going to sleep here with you,” he says.

“Umm…”

“I wouldn’t want you to sleep back here alone. It’s scary back here, and I don’t want big brother to have a bad dream.”

“I think I’ll be all right,” I say, ducking under the tent's mesh flap and zipping it closed before stepping over him to the empty sleeping bag. Lying down, I take a flashlight and a copy of Paul Theroux’s The Pillars of Hercules before reading.

“Hey, big brother,” he says, sitting beside me. What are you reading? Can you read it aloud to me?”

“It’s in English,” I tell him. “I don’t think you’d understand.”

Undeterred, he stares up at me expectantly. Feeling his eyes on me, I put the book down. For a moment, I stare up at the tent's canvas, thinking this is a bizarre situation.

After a while, I turn and look at him. He is still staring at me from inside his sleeping bag.

“Hey,” I say. “Would you mind if I called you ‘Short Round?’ Or maybe just ‘Shorty?’”

He seems to think about it for a moment.

“I don’t think so,” he says. “What’s it mean?”

“There’s a great movie you should see someday,” I tell him. It's called Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. The boy in that movie is called Short Round and looks a little like you. He fights the bad guys, jumps out of a plane, and can even drive a car.”

As I tell him this, his eyes go wide.

“Wow,” he says. “Wow.”

“I know,” I say. “It’s incredible.”

We fall silent, and I stare through the tent's front flap mesh. The candles flicker on the altar, and the hermit stares back at me impassively.

“Hey big brother.”

“What’s that?”

“You can call me Shorty. I don’t mind.”

“Okay. I will.”

“Thanks. Goodnight, big brother. Have a good dream.”

“Goodnight, Shorty. You too.”

* * *

In the morning, the two of us walk back down the long staircase to the monk’s quarters at the foot of the cliff. Today, Shorty leads me to the far side of the house, where tall grass surrounds the garage. The monk stands out in front and motions for us to help ourselves with fried fish, curry, and rice on a small table.

Shorty and I help ourselves, eating in the early morning sunshine. After we finish, I take our plates and wash them out with a nearby hose before putting them in a bus pan sitting by the back door to the house. When I turn back around, the monk stands right before me.

“Can you drive?” he says. It is the first thing he’s spoken to me since my arrival yesterday and the first thing I’ve been able to understand.

“Um,” I say. “I mean — yes.”

“Good,” he says, handing me a set of keys. He walks over to the metal garage door and leans over, gripping the handle with both hands. He slides the door open with a solid upward pull, revealing a brand-new-looking Toyota Fortuner inside.

“Okay,” he says. “You pull the car out and I’ll close this up behind us.”

I nod and do as he says.

A few moments later, I find myself sitting in the car with the two of them — Shorty in the back, the monk in the passenger seat, and me behind the wheel. Up above, the sun is already high in the sky, shining down through the verdant canopy of the trees.

“Turn right out of here,” says the monk. “And you’ll go all the way until we pick up the main highway to Surat Thani. I’ll tell you when we’re getting close.”

With that, he closes his eyes and seems to fall asleep instantly. I look in the rearview mirror. Shorty is stretched out across the back seat, also enjoying a mid-morning nap.

Shaking my head, I put the car into gear and pulled onto the dirt track.

* * *

I drive for about forty-five minutes with both hands on the wheel, feeling like I’ve been entrusted with precious cargo. Neither the monk nor Shorty wear seatbelts, making me anxious even though this is an everyday occurrence among Thais. Still, I wonder what might happen if we were to get pulled over. It would undoubtedly look bizarre, and I figure it is probably illegal — a young farang guy without any proper Thai or international driving license chauffeuring an old monk and a novice. But I realize it’s perhaps mai pen rai; there’s nothing to worry about. The presence of the old monk in the car would ensure that any police officer would look the other way.

I think about this for a moment — how the entire fabric of Thai society is affected and made warmer by a population that has a deep reverence for its elderly, and especially for those whom they consider to be wise, even holy. Such values differ from back home, where wisdom and grace are not valued as qualities in and of themselves but only when tied to financial might or political power. This is why people like the Dalai Lama must be born in Asia. Because if they were born in America, they’d never make the news.

“Take this exit,” says the monk, snapping me out of my reverie. I merge onto the off-ramp, and after a few more turns, we pull into Tha Ngiw Hospital's back entrance.

* * *

After parking the car, a doctor in a white coat meets us at a small service entrance at the back of the hospital. The doctor and the monk briefly chat before he turns to me and shakes my hand, speaking in English.

“Welcome,” he says. “I’m Dr. Thongdee, the director of Tha Ngiw Hospital. Come in, we have a change of clothes for you.”

As we walk through the entrance, a nurse approaches me with a pair of scrubs. Behind her is a swinging wooden door, damp with moisture, with a sign above it in both Thai and English:

อบตัวสมุนไพร

Herbal Sauna

“Put those on, and meet us back here,” says the doctor before he, the monk, and Shorty set off down the hallway.

The nurse opens the door to a small changing room and then motions for me to go inside. I close the door, change into the scrubs, and fold my clothes into a small pile before walking back outside. A few minutes later, everyone reappears, wearing identical scrubs.

“Okay,” says the doctor, opening the door to the sauna. “If you get too hot, or you feel faint, just let me know.”

We go in and take seats on the damp wooden benches. I sit next to Shorty, and the monk and the doctor sit across from us. On the floor between us are four buckets, each about a foot tall, all filled with an opaque, dark-brown liquid. The nurse follows us inside, pouring water over a barrel of hot coals. There is a loud hiss, and fresh steam fills the room. Another nurse appears holding a tray, and she hands everyone a glass of red juice. I take a sip. It is sweet but with a mildly tart aftertaste.

“Roselle juice,” says the doctor. “Full of antioxidants.”

He puts his bare feet into one of the buckets of dark liquid. The monk and Shorty do the same, and I sit there, wondering if I should follow suit.

“That,” says the doctor, motioning towards the bucket in front of me, “is a solution containing the essential oils distilled from the wood of a specific kind of tree, indigenous to the south of Thailand.”

The doctor looks over at the silent monk and then back at me.

“The monk began growing these trees years and years ago, in the jungles outside his cave,” says the doctor. “Long before we had any idea that the oils from this particular tree were powerful homeopathic agents that could be used in combating cancer, as well as for promoting overall health. Long before we knew any of this – he knew.”

I dip the heel of my right foot into the dark liquid, testing it. It is hot, but otherwise, it feels like regular water. Slowly, I lower both of my feet in. Seeing this, the monk smiles.

“About a year ago,” says the doctor, “there was a woman who came to be treated here. She was very sick with breast cancer, and the doctors at Siriraj Hospital in Bangkok had given her one month to live. When she came, it was clear why they had given her such a prognosis. She was very weak, and could barely walk. But we managed to treat her here for eight weeks, before she left and went back to Bangkok.”

Shorty’s feet splash in the bucket, and the steam hangs like a veil.

“You mean she was cured?” I say in disbelief.

“Completely healthy,” says the doctor. Then the monk says something to him in southern Thai, and they both grin.

“He wants me to tell you the best part,” the doctor chuckles. “As this woman left the hospital, the monk handed her an envelope containing two hundred baht. At first, she was confused by the gesture, but the monk said to her, ‘When you get back to Bangkok, I want you to use this money to get a taxi to Siraraj Hospital. Just stop in there briefly, and see your old doctors. Tell them thanks for all their help and advice, but you’re doing just fine now.’”

Upon hearing this, the monk grins before they exchange a few more words.

“He says,” explains the doctor, “That he wishes he could have seen the look on those poor doctors' faces. When they saw that woman, they probably thought they were seeing a ghost!”

Then the monk slaps the doctor hard on the thigh, and the two burst into uproarious laughter.

* * *

We eat a simple dinner of shrimp fried rice at the monk's quarters before washing up and heading to bed. I return to the tent and read for a few minutes by flashlight. It isn’t long before Shorty reappears, sidling up next to me once again.

“Did you have fun today?” he says.

I put my book on my chest and stare at the candles flickering on the altar.

“I don’t know if I would call it fun,” I say. “It was interesting. I just don’t know what to think of it all.”

Shorty doesn’t say anything, but he seems to be listening.

“I studied biochemistry in college,” I tell him. “And from what I learned there, I should be comfortable dismissing the kind of medicine the monk and the doctor practice as a bunch of nonsense. And yet…there’s something about them. Maybe it has to do with their good nature, or their sense of humor, but whatever it is, they’re both very charismatic. I imagine there must be a lot of people who find them strange, and I bet that for everyone out there who believes in them, there are probably plenty more who want to discredit what they do. But one thing’s for sure — they’re impossible to ignore.”

Shorty remains silent as if prompting me to go on.

“I guess the thing I find really strange is that, in spite of all my background knowledge, and my upbringing – there’s a part of me that can’t help but believe.”

I look down at Shorty, who rolls onto his stomach before lifting himself onto his elbows.

“Well yeah,” he says, looking up at me. “The monk knew big brother was a believer even before you got here.”

I stare at him.

“What are you talking about?”

“That’s why he brought you here,” he says. “He only brings people here who he knows will believe.”

His words take me aback, and his voice seems to echo in the damp silence of the cave. Who he knows will believe…

“But why?” I say. “I mean, it’s a nice honor. But whether I believe or not — I’m going back to America next week.”

"We know,” says Shorty. “But you’re a writer, right? The monk said that after you went home, you would write all about this. And that maybe one day people might read what you write, and it might help them to believe, too.”

Upon hearing this, time slows down. The boy’s words are like a key, unlocking something inside of me that, until now, I had only vaguely intuited was there. And yet this vague intuition had led me here and had willed me to cut myself off from home and family for all these years. I remember when I left and thought I could leave everything and everyone behind and remake myself how I wanted without all the burdensome expectations of my culture. And while all my time spent in this place had remade me, I suddenly see that the transformation had never been of my own doing. It had always been Thailand, working on me slowly and gradually, like waterworks upon a stone. And now, underneath all my rough and unfinished edges, a nascent form or shape was beginning to appear. A writer? I was still uncomfortable talking about these aspirations with others, let alone referring to myself as a writer in public. But after years of wrestling with a foreign tongue, navigating Bangkok by motor taxi and canal boat, and baking in a southern Thai sun, I believed in myself more than I ever had in the past. Maybe this was Thailand’s great gift to me or my reward for opening myself up to her — the ability to question if perhaps everything I had ever been told about what’s possible in life might all be wrong. That maybe the life I was beginning to dare to imagine for myself was not only possible but the only thing worth striving for. And maybe, like a woman who beats cancer in a southern Thai jungle, the most powerful thing I had at my disposal was my ability to honestly believe.

“So when you write about us, make me really handsome, okay? And really strong. And I want to drive a car, like the boy from Indiana Jones. Maybe you can say that I drove us to the hospital at two hundred kilometers an hour, when we were being chased by bad guys…Okay, big brother?…don’t forget about us, because we’ll miss you…we’re really gonna miss you…”

The candles on the altar burn out, and I feel myself slipping away. The sand underneath the tent feels good against my body. I begin to wonder if this is a dream, if all of this has been a dream, and I am lying asleep at the bottom of the Andaman Sea, staring up at the waves.

It won’t be long now as a Thai sunset cascades through the blue.

You’re on your way home.

|

|

The author is in the monk's cave before his return home.

|

Upon graduating with his degree in chemistry from the University of Delaware in 2009, Paul King moved abroad to Thailand, where he lived, studied, and worked for three years. He returned home to the US in 2012.

|