Moving to China to Work and Live

Basic Considerations

By Victor Paul Borg

|

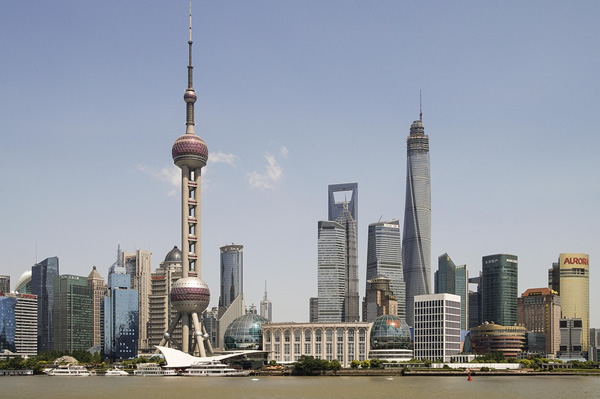

| Shanghai skyline. |

There are two countries in the world whose culture has the historical depth, confidence, and population spread to make them hold-outs in a world that is increasingly homogenous, and those are India and China. Both are attractive in different ways for Westerners seeking experience living and working in a different culture. China, the subject of this article, attracts foreigners by its past and present profile: an old eastern culture that is rapidly rising to take its place among the world’s greatest modern civilizations, a stature that is all the more intriguing given the way it is blazing its own path in terms of the social contract. Do not be dissuaded by an element of bad press in the West; news tends to wallow in the alternative reality of political drama, while the realities on the street are something quite else. Chinese people are indeed largely welcoming and open, and opportunities abound for the astute.

Yet China is not easy. Food will often seem strange for the foreigner, different ways of doing things, different social contracts and expectations, uneven levels of development and modernity, and the widespread inability to communicate in English all combine to make China a hard country to move to. But for those who brave the adversities, and immerse themselves into China, the rewards are undeniable — at the very least you learn something about different ways of seeing and something about a culture that has been innovative throughout much of its history.

Work and Study in China

Unless you gain placement in China as a representative of a multi-national company or a correspondent for a newspaper, the work opportunities in China correspond with the expertise needed in certain areas. Certain industries that require foreign experts are upscale hotels (working as a chef, or mid-level manager), marketing organizations (expert marketers), and advanced industries (who need scientists). For all these posts you obviously need to possess a skill that is in short supply in China; if you do not, the only other way is to teach English. It is easy to find an English-teaching job: demand often outstrips supply, and English teaching jobs can be found anywhere in China whether in big or small cities (or towns).

A lot has been written in TransitionsAbroad.com about the

readily-available option to teach

English in China, and instead of covering the same ground

here, I will focus on the wider issues that come into play

when working and living in China. One thing you should note

is that salaries vary from school to school, and region to

region — in some touristy regions, which is where the

supply of eager teachers is high, salaries can be relatively

low compared to the cost of living. But move inland, to a

small city or town, and you can bag a salary that puts you

among the top earners in the city or town. Yet generally

speaking, anywhere in China salaries are relatively high,

and you will be earning an amount of money that elevates

you to upper the middle class in terms of income.

For most people, teaching English is necessarily

part of a long-term career, and you can

use English teaching in China as a means to an end. It could

be something you do for a few years to experience the country

and culture. Or it could be a stepping

stone to other international careers: you get into China

teaching English, learn the language and the culture, make friends,

and then discover other opportunities. Stories abound of former

teachers who, after a few years, move on to more career-minded

jobs, or start their own business.

Of course, anyone can move in to work on a business in the first place. The laws for doing business in China are favorable, but that is only part of the story. For unless you are a multi-national company, or if you possess a lot of money with the resources to move in and make things happen in a big way, then doing business in China requires patience. To create a successful small business you need to understand the culture, identify a niche, and have a good partner or friends (who can help you find opportunities and manage the bureaucracy).

Another opportunity for moving to China

is to study, mostly taking a course in Chinese

language and culture. This is the ideal way of learning

about the culture and experiencing the country, but it also

presumes that you have money to spare for paying for tuition

and living costs. Internships

in China present another great option to learn about working in the local business environment while learning the language and exploring the culture. The experience will include personal working

and learning experiences that help build

the resume and often lead to great jobs down the road.

Where to Move and Live in China

China’s development is uneven; some coastal cities — particularly Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou — are modern metropolises where the culture shock is limited. In these cities, you will find western ingredients in supermarkets, western-style bars and clubs, a relatively significant amount of Chinese who can speak English, and many other expatriates (for example, 300,000 foreigners live in Shanghai, the city with the greatest concentration of expats). Thus it is easier to move to these cities. One downside is a relatively higher cost of living, but the biggest trap may well be that you can easily get caught up in the classical expat way of life — your friends and social groups would mostly be other expats or Chinese people who want to be like foreigners, and therefore you do not learn much about China’s culture and the Chinese way.

If you really want to experience a form

of Chinese culture that is more intact and traditional, then

look east. You can opt for the second tier cities such as Chengdu,

Kunming, Xi’an,

and many others, or you can go more local and put your sight

on smaller cities where people have not yet had the chance to

mix with foreigners. These are cities in inner provinces, as

well as small cities or towns in coastal provinces — cities

that, despite their insularity, are still full of people eager

to learn English and government schools that require “native

English teachers.” In these kinds of places, you have no

choice but to blend in as there will not be other foreigners

(or very few) you can mix with.

Of course, settling into smaller cities is harder because of cultural differences. You will not find any authentic western restaurants in these cities (aside from the ubiquitous McDonald’s), and it will be hard to make friends unless you can speak Chinese. Therefore you need perseverance and patience, but ultimately the rewards are higher. For once you speak some Chinese, making friends with Chinese is easier than in the modern coastal cities where foreigners are common. You will be treated as novelty material, and you will find many local people who are eager to be friends with you. Young educated Chinese are eager to have foreign friends for a variety of reasons: curiosity about foreigners, an opportunity to practice English, gain exposure in dealing with foreigners, learn things from foreigners, and perhaps make a friend who could be helpful if the opportunity to move to a Western country arises (many young, educated Chinese would move to a Western country if given a chance, mostly due to better salaries and standards of living). So making friends is relatively easy, but everything else will be strange: the way people eat, social interactions, and day-to-day language barriers (you are unlikely to find anyone who can speak English when you might need to fix your telephone line, install an internet service, buy shoes, or do other daily chores of life).

Settling into Life in China

If you are employed by a Chinese company, or you are a new teacher, then your employer will help you find an apartment. You need this help: on your own steam, you will only be able to find an apartment in the three modern coastal cities of Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou, and even in these places it’s difficult to assess what you are getting and for what without help from local Chinese people. A local person would also help you assess the suitability of any given area for access to public transport, going out, shopping for food, and whether the area is safe or not. Bear in mind that your relatively-good salary and the low cost of living in China will mean that you can afford a comfy place in a good area wherever you are in China.

But all of this should be of little concern if your move to China is going to be facilitated by contacts on the ground, whether that’s an employer or friends that will help you set yourself up. And you need someone to get you started in China — if you are thinking of simply getting a visa, going over without any contacts, and then setting yourself up and finding work… well, it can be done, but it will mean a few months of difficulties, frustrations, and perhaps loneliness. You can accomplish a move to many countries — I did it in England and Thailand and Australia, for example, just moving over by myself — but China is more complex.

If you want to make your transition as smooth as possible, avoid hassles, and keep the cost of living down, then you can do yourself a great favor by forgetting the meaning of comfort food. Western foodstuffs in China can only be found in large supermarkets in large cities, and these foodstuffs are expensive by Chinese or Western standards — you could easily be paying double or more the price you pay at home for ingredients such as bacon, butter, and cheese. So forget about these ingredients, and learn to love and cook Chinese food — it is not so hard, and Chinese food is delectable. And neither is cooking so hard: all supermarkets are full of pre-packed sauces where you simply need to add the main ingredient, like chicken or fish, and water and cook a great meal.

What Visa to Get

If you find employment in China, you will get a work visa — called Z Visa — and this will be arranged by your employer; if you study, you get a study visa for the duration of your course. So far, so obvious, but there is one type of visa, an F Visa or Business Visa, that merits discussion. Officially, this visa is issued for people who are in China on short-term business trips: to buy or sell, to do some kind of short assignment work in Chinese companies, and to explore possibilities of doing business or developing business partnerships in China. Yet the ease with which this visa has been issued and the laxness of the paperwork has made it the visa of choice for an assortment of foreigners staying in China. There are freelance writers, employees in charities or organizations, English teachers, consultants in a variety of industries, travel bums, as well as freelancers who work in a variety of industries who have spent many years in China on a business visa. These people do not even have to apply for visa renewals themselves: specialized visa-procurement agencies handle all the paperwork, and get you an F-visa, normally for one year at a time.

Yet there is a catch. Since most people would not be strictly adhering to the conditions of the visa, their visa is only as good as the Chinese government decides to close one eye. And the Chinese government decided, before the Olympics, to suddenly start stringently enforcing the requirements for the F Visa and also to tighten the policies or criteria in the issuance of all visas. For this and other reasons, it is always wise to check with your country's Embassy to China for the latest rules before your departure.

Note: For part 2 of this 2-part series, see Moving to China to Work or Live: Cultural Immersion.

Victor Paul Borg has been living in Asia for several years, and his writing and photography is published around the world.

|