Good Travel is Thoughtful Travel

by Rick Steves

|

|

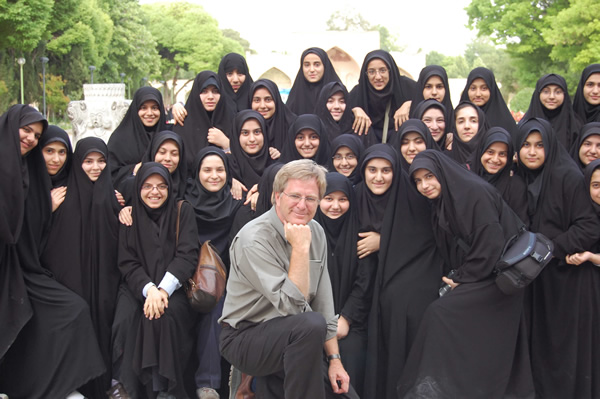

Rick Steves hanging out with schoolgirls in Iran. Photo courtesy of RickSteves.com.

|

As a kid my image of travel was clear. It was hardworking people vacationing on big ships in the Caribbean. They’d stand on the deck, toss coins over board, and photograph what they called “little dark kids” jumping for them.

As an idealistic student, I wondered if I should make teaching travel my life’s work. I questioned whether travel in a hungry world was a worthwhile activity. Even today, travel remains a hedonistic flaunting of affluence for many — see if you can eat five meals a day and still snorkel when you get into port. On cruise ships, the cultural primer for the port du jour is little more than a shopping tip sheet.

I was raised thinking the world was a pyramid with the U.S. on top and everyone else trying to get there. I believed our role in the world was to help other people get it right…American style. If they didn’t understand that, we’d get them a government that did. My country seemed to lead the world in “self-evident” and “god-given” truths. But travel changed my perspective.

My egocentrism took a big hit in 1969. I was a pimply kid in an Oslo city park filled with parents doting over their adorable little children. I realized those parents loved their kids as much as my parents loved me. From that day on, my personal problems and struggles had to live in a global setting. I was blessed…and cursed…with a broader perspective.

That same year travel also undermined my ethnocentrism. Sitting on a living room carpet with Norwegian cousins, I watched the Apollo moon landing. Neil Armstrong took “ett lite skritt for et menneske, ett stort skeitt for menneskeheten.” While I waved an American flag in my mind, I saw this was a human triumph even more than an American one.

In later years I met intelligent people — nowhere near as rich, free or blessed with opportunity as I was — who wouldn’t trade passports. I witnessed stirring struggles in lands that found other truths to be self-evident and God-given. I learned of Nathan Hales and Patrick Henrys from other nations who only wished they had more than one life to give for their country.

I saw national pride — that wasn’t American. When I bragged about the many gold medals our American athletes were winning, my Dutch friend replied, “Yes, you have many medals, but per capita, we Dutch are doing five times as well.”

Travel shows me exciting struggles those without passports never see. Stepping into a high school stadium in Turkey, I saw 500 teenagers thrusting their fists in the air and screaming in unison, “We are a secular nation.” I asked my guide, “What’s the deal…don’t they like God?” She said, “Sure, they love God. But here in Turkey we treasure the separation of mosque and state as much as you value the separation of church and state. And, with Iran just to our east, we’re concerned about the rising tide of Islamic fundamentalism.”

Good travel is thoughtful travel — being aware of these national struggles. In Berlin I helped celebrate the opening of Germany’s new national parliament building, the Reichstag. For a generation, it was a bombed-out hulk stranded in the no-man’s-land separating east and west Berlin. But today the building is newly restored and crowned by a gleaming glass dome. The dome — free and open long hours — has an inviting ramp spiraling to its top. The architecture makes a powerful point: German citizens can now literally look over the shoulders of their legislators at work.

Climbing to the top of this great new capitol building (now called the Bundestag rather than the Reichstag) on its opening day, I was surrounded by teary-eyed Germans. Any time you’re surrounded by teary-eyed Germans something extraordinary is going on. Traveling thoughtfully, I was engaged…not just another tourist snapping photos, but a traveler witnessing an important moment in history as a great nation was symbolically closing the door on a terrible chapter in its history. After so much war, fascism, communism, and division, a wiser Germany was entering a new century united and free, and filled with hope.

Travel teaches the beauty of human fulfillment. As you travel you find people who make crepes like they invented them…and will make them that way all their lives. Being poured a glass of wine by a vintner whose family name has been on the bottle for over a century you feel the glow of a person fulfilled. Sitting above the congregation with an organist whose name is at the bottom of a 300 year-long list of musicians who’ve powered that cathedral with music, you know you’re in the presence of an artist who’s found his loft.

On the border of Iraq I have vivid memories of another lesson in fulfillment. A weather-beaten old Kurd held his chisel high in the sky. He was the region’s much-loved carver of prayer niches for village mosques. The world was brown and blue — his face, his robe, the parched earth, and the sky. The blade gleamed as he declared, “A man and his chisel…the greatest factory on earth.” The pride in a simple man, carving for the glory of God, was inspirational. He was fulfilled. When I asked the price of a piece he’d carved, he gave it to me explaining for a man his age, to know that a piece of his work would be enjoyed in America was payment enough.

Travel helps us celebrate differences and overcome misunderstandings — big and little — between people. Recently in Germany a little pre-schooler stared at me. Finally his mother said, “Excuse my son. He stares at Americans.” She went on to explain that last time they went to McDonald’s the boy (munching the fluffy hamburger bun) asked why Americans have such soft bread. She explained that it’s because Americans have no teeth. Giving the child a smiley growl, I did my part to dispel that misunderstanding.

On another trip I was in Afghanistan. Eating lunch in a Kabul cafeteria, my meal came with a lesson in pride and diversity. An older man joined me, intent on making one strong point. He said, “I am a professor here in Afghanistan. In this world, one third of the people use a spoon and fork like you, one third use chopsticks, and one third use fingers — like me. And we are all civilized the same.”

Travel paints a human face on our globe, making the vast gap between rich and poor vivid. Half of humanity — three billion people — is trying to survive on roughly $2 a day. Educated people the world over know that America, with 4 percent of the global population, controls half its wealth. And most of the world believes we elected a president whose mission is to make us wealthier.

My hard work and business success have made me wealthy. I wouldn’t be where I am today if it wasn’t for the freedom and opportunity that comes with being an American. Without America‘s commitment to freedom, those teary-eyed Germans might still be under fascist or communist rule. In fact, without America, we might live in a world without guidebooks and bus tours.

Travel has sharpened both my love of what America stands for and my connection with our world. And lessons I’ve learned far from home combined with passion for America have heightened my drive to challenge my countrymen to higher ideals. Crass materialism and a global perspective don’t mix. We can enjoy the fruits of our hard work and still be a loved and respected nation. While I’ve found no easy answers, I spend more time than ever searching. The world needs America the beautiful. But lately, the world sees America as more aggressive and materialistic than beautiful.

Europe is also wealthy. But it gives capitalism a compassionate twist — a safety net for the losers — even if it weakens the incentives of pure capitalism. It’s tough to get really rich in Europe. Belgians like it when their queen does her own shopping. The Dutch say the grain that grows the tallest gets cut back. Norwegians unilaterally forgave the debt owed them by the poor world.

We’ve fooled ourselves into thinking we are a generous nation. But the aid we give to poor countries around the world amounts to one-eighth of 1 percent of our national income. While we are the wealthiest nation, our allies give much more to the poor. Most of our “aid” is military aid to allies like Israel. Take away that and we’re a perennial last place among wealthy nations.

My European friends amaze me with their willingness to pay huge taxes and live with regulations I would chafe at. And, with all the regulations, expenses, and safeguards for society and workers in Europe, it’s not a place I’d want to run my small business. But it’s a place that challenges me to see how a society can build compassion into its affluence.

Hiking high in the Alps, I asked my Swiss friend Ollie why they are so docile when it comes to paying high taxes. Without missing a beat he replied, “What’s it worth to live in a country with no hunger, no homelessness, and where everyone has access to good health care and a top-quality education?”

Europe is investing in its infrastructure. And travelers know the results are breathtaking. With the English Channel tunnel, trains speed from Big Ben to the Eiffel Tower in 2.5 hours. More travelers now connect London and Paris by train than by air. Norway is drilling the longest tunnels on the planet — lacing together its fjord communities by highways. There’s a bullet train in Spain. And every year it seems new autobahns, tunnels, and bridges cut a couple of hours off the time it takes my tour buses to make our 2,000 mile Best of Europe circuit.

European money is making this happen. The European Union — a vast free trade zone — is investing in its weakest partners. And European governments are progressive on the environment. Entire communities (with government encouragement) are racing to see who will become the first to be 100 percent wind-powered.

Europeans don’t have the opportunities to get rich that Americans do. And those with lots of money are highly taxed. But Europeans consume about a third of what Americans do and they claim they live better. Most Europeans like their system and believe they spend less time working, have less stress, enjoy longer life spans, take longer vacations, and savor more leisurely (and tastier) meals. They experience less violence and enjoy a stronger sense of community.

Through travel we learn how the world views America. The majority of Europeans see American foreign policy as driven by corporate interests and the baffling needs of small segments of the electorate. No other major nation is routinely outvoted in the U.N. 140 to four. Our refusal to join with the family of nations in fighting global warming, cleaning up land mines, and supporting the world court is telling. To Europe, American unilateralism is a euphemism for American imperialism.

Yet, in spite of all these hard truths, I know I live in a great corner of the world and have much to be thankful for, to defend, and to be involved in. By connecting me with so many people, travel has heightened my concern for people issues. It hasn’t given me any easy solutions. But it has shown me that the people running our government have a bigger impact on the lives of the poor overseas than they do on my own life. It’s left me knowing that suffering across the sea is as real as suffering across the street. I’ve learned to treasure — rather than fear — the world’s rich diversity. It’s clear to me that people around the world are inclined to like Americans. And I believe that America — with all its power, wisdom and goodness — can do a better job of making our world a better place.

Rick Steves writes European travel guidebooks and hosts travel shows on public television and radio. His 50-plus books on European travel are available at bookstores and at www.ricksteves.com. Rick is also very involved in social activism and has written and spoken widely on the subject.

Note from the Editor: Rick Steves' very powerful book Travel as a Political Act is one of the important books on ethical engagement and self-awareness as a traveler and global citizen. From this section of his site you may find many of his other expressions of incessant committment to ethical travel and global issues relating to social responsibility, including this recent blog post A Rick Steves Book Report: Strangers in Their Own Land (Anger and Mourning on the American Right).

|