Turkey, Blindness and a Philosophy of Slow Travel

Article and photos by David Joshua Jennings

When I walked in on the Turkish man in my Amsterdam hostel dormitory, he stared at the ceiling. There was obviously something wrong with him.

His ear followed me across the room, and when it heard me pull out a chair, he stumbled over and offered me a cigarette.

“It’s rolled with apple tobacco,” he said. “Tastes awesome.”

The room was foggy and stunk like a gym locker. It was 3 p.m. Here and there, among the bunk beds, a bare arm or leg hung out from under a blanket.

The Turk lit up and blew the smoke out side-mouthed, his eyes rolling around like puppet eyes. They were bloodshot and small, like lizard eyes.

“How many did you drink?” I asked.

“Alot. Three.”

“Three? You’re brave. I can only handle one.”

I couldn’t stop staring at his eyes.

“Your eyes are crazy,” I said. “You must really be out of it.”

“I’m blind,” he said.

A teenager emerged from beneath a mound of blankets and wandered like a zombie into the bathroom.

The Turk handed me the cigarette. I apologized for saying that about his eyes. I spent a few minutes feeling bad about it. Then I realized he couldn’t see me and relaxed.

I stared at him. I discovered I could explore his face in ways impossible with a seeing person. I examined his lines and pores, his whiskers, especially his eyes.

His name was Göktürk, which means “Sky Turk.” Although he was born in Istanbul, where everyone calls him German, he has lived most of his life in Germany, where everyone calls him a Turk. He was the first Turk I’d ever met and served as my introduction, however partial, to the idea of Turkey.

He’d been traveling around Europe for a few months, sight-hearing, sight-smelling, or whatever blind people do when traveling. I couldn’t understand what they could do at the time or why a blind person would travel. For me, nearly all the enjoyment of travel was somehow tangled in sight. One traveled to see things, things inaccessible to people who are blind. Theirs was a world of pure dark spaces, and the hardship of traveling didn’t seem worth it.

“There is a Turkish proverb,” Göktürk said in response. “He who doesn’t pray has no ears for the call to prayer.”

There was a whole world out there that I had yet to smell or hear. The sight had been eclipsing my other senses. Without sight, Göktürk said, the other senses open like flowers.

“People tell me about what they see, and I cannot imagine,” he said. But I feel things that, when I tell them, it’s like they don’t exist for seeing people — things like a smell face.”

Every human apparently has a unique smell face — this is how Göktürk recognizes people without hearing their voices. The same goes for a city, a village, or a country. Each new place was an evocative world of new odors. He asked me to imagine the wave of color The Seeing might experience when they go to India for the first time. It was the same for him but with sounds and smells. Each place had its own smell and soundcloud.

“It must be crazy,” I said. “How you are right now, and being blind.”

“I’m feeling sensations, something like colors maybe, very intensely.” He stood up and stumbled towards the window. “You see where the light falls through the window?” He moved his hand into the shaft of sunlight. “I can feel the changes in heat, and how the light spreads out.” He made a hoop of his fingers around the light shaft and followed it down as if it were a solid pillar to the wall. “I can feel the light hits here,” he said, tapping on the square of light on the wall. “And from there reflects out,” he made a vast gesture of his arms. “Across the ceiling like waves.”

“And sounds are as strong as the color feelings,” he continued. He held his breath. “I can hear water splashing in the canals outside, and bicycle bells. I can hear you breathe, and maybe even your heartbeat.” He took a whiff of air. “And it seems I can smell everything, like the dirt in the carpet, and mouse droppings. And food in my beard. I can smell the different smells of everyone in the room, and where they’ve been, and what they’ve eaten.”

Göktürk put on his jacket and threw out a jumble of rods which snapped together into a walking stick.

“I’m starving,” he said. “I’m going for hamburgers. Want one?”

“I can go for you,” I said. “You’re messed up, and you’re… blind. What if you fall into a canal?”

“I hear where the canals are,” he said. “In Europe it’s not so hard being blind. The crosswalks make beeping sounds, and the Euro comes in different sizes, so I know what bill I have in my hand. I’m fine traveling here.”

When he left, everything in the room seemed a little altered by what he’d told me. Then I tried it, and I shut my eyes. A new world of odors sprang forth as though they’d been hiding, as though I’d finally tuned into something.

Now I have opened my eyes and am in Istanbul, a nargile café called Can. I’m inhaling a cloud of smoke through a nargile tube. The aroma of apple tobacco evoked the memory of Göktürk.

Outside through the window, the Bosphorus gleams like a mercurial ribbon. Beyond its waters, the sun falls behind Sultanahmet Hill, raising the silhouettes of a dozen minarets like dark swords. In this café, because of the stagnant, smoky air and the dreamy slowness of movement, time seems to have lost all meaning. No clocks hang on the wall. If they once did, perhaps they’ve melted.

I fog smoke from my nostrils and watch it dissolve as I lean forward from the indentation I’ve introduced to a beanbag and wearily slide another backgammon token across the board. My opponent, who left to buy salep, a hot drink made from orchid flour, some twenty minutes ago, hasn’t returned. I don’t mind. It takes about an hour to smoke a pipeful of tobacco from my nargile. The smoke is cool and elating, and I would like to reflect upon this memory.

Göktürk springs out like a jack-in-box every time I whiff apple smoke, dragging a complex web of memories behind him. It was four years ago I met him.

Though many short conversations and chance events have recast my life, I consider my encounter with Göktürk particularly important. In my memory, he is larger than life, something akin to Odysseus.

When Göktürk returned from getting hamburgers, we talked for a few hours. After that conversation, I realized I could never again whine about the hardships of travel. Whenever I’ve been followed or stared at, harassed because I’m American, or couldn’t sleep because a slimy rat ran over my leg in the darkness, I remember Göktürk. He went through all that ages ago, alone, without sight.

However, the most important thing he showed me was how to slow down, widen my awareness, and experience the world imaginatively. A day, a night, a clock, a country — Göktürk showed me these things only had meanings others had given them, which I had inherited and could disfigure by seeing how blind people see them. He’d personally never seen such things as a clock or a calendar. Their artificiality was obvious to him.

Never before Göktürk had I closed my eyes and allowed my other senses to feel their way around an environment. Now that I do, I find the world awash with odorant molecules (the average human can recognize up to 10,000) emanating from trees, flowers, earth, animals, food, machines, and other humans.

I close my eyes. I sniff the air.

First, I smell smoke — the glowing charcoal atop the tobacco plug of my nargile sizzles the apple and hot molasses into vapor and interfuses it with the low tones of damp tömbek gurgled in bubbles through the water. From the mild-eyed Turks smoking nearby, I smell cherry licorice and what seems to be cappuccino and foamed cream smoke. The steamy fragrance of tea rises from their tulip-shaped glasses, and a waiter passes carrying a trey, the aroma of spiced cocoa stretching behind him like a comet’s tail.

The room has a distinct scent, the dusty smell of an old book. The beanbags scattered across the floor as fat teardrops smell like human sweat and smoke, chemicals shed off living bodies from Turks, Kurds, Greeks, Armenians, Germans, Iranians, and Iraqis, and catapulted back into the air every time someone plunks down on one. It smells like Christmas Eve night in a log cabin in the Orient a thousand years ago.

Startling to think these chemicals are swallowed every moment by my nose. The girl in the headscarf a few beanbags down has a bouquet of odors evaporating off her as I write this. The waiter passes, stirring a light breeze, and her molecules fly through the air like lock-armed skydivers and are engulfed by my nostrils. She becomes a part of me.

This activity, nargile smoking, slowing down, lounging in a salon for hours, smelling things, reflection — to understand and feel the concept of time behind these acts, one must know how they are woven into the fabric of the Turkish culture that has been inhaling me for a year now.

There are many other aspects of modern Turkey. Look outside and see a bustling market where fake brand-name shoes are sold alongside a panorama of locally grown fruits and vegetables. Headscarved women will be shoving between the aisles, squawking at one other like hens. You may see a Starbucks, a Burger King, Nigerians hocking watches, businesswomen wearing thigh-high slips and lipstick, and older men smoking cigarettes so forcefully it seems they’re trying to suck genies through the filter.

A parade of cars might pass, with bearded men hanging out the windows, honking, waving Turkish flags, and calling for the liberation of Palestine.

So, I’m not trying to make generalizations. I’m getting down to the essence of a ritual whose understanding demands time and a certain state of mind and being. It’s an understanding of an organic sense of time, not the mechanical ticking of watches but the sort of time associated with growing chin hair or the menstrual cycle, the kind of time many backpackers, obsessed with racing through as many countries as possible, do not take the time to understand. This sense of time has often been associated with the Orient. Whether that’s just an illusion, I don’t know, but let’s explore it.

The nargile I hold has long been a symbol of this Orient. It’s easy to observe this in nineteenth-century Orientalist paintings, where Ottoman men are often depicted lounging in sedirs with their nargiles, and harem women, among their draperies and ornate carpets, dreamily puff from the serpentine tubes. To stare at this nargile, study it, lose time altogether, and pay full attention to this one object would be to embody the sort of time I’m talking about.

This nargile has long been an object of mystery. It can combine in one piece of equipment the ephemeral nature of smoke, often associated with the spirit, and water, a symbol of the unconscious mind. It’s an instrument that inspires a total bodily movement, an experience with its laws. This ritual rejects the screaming rush of urban life and becomes a metaphor for life itself. The smoke is one vast ethereal unity until the lung heaves it through the water, where it becomes an encapsulated unit, a bubble, a soul, which is inhaled by and inhabits the body for a time before vanishing back into dispersion.

I close my eyes. I listen.

I hear the gurgling smoke of a dozen nargiles. Here and there, dice clatter across a backgammon board. The conversation is hushed and occasional, sometimes a gentle wave of laughter. A fog horn moans from afar as a ferry tugs down the Bosphorus. A waiter’s feet pad across the carpet as he stirs a tin of charcoals with metal pincers. Outside, the wind howls, and the café’s outer canvas flaps up like a raven’s wing.

Herman Melville once remarked, “These Turks smoke like conjurers.” It’s a quintessentially Turkish habit. The government recently attempted to combat this stereotype by banning smoking in most public places, including all forms of public transport. However, I have yet to enter a bar or restaurant where this law is enforced. I routinely see bus drivers light up when there’s a lull in traffic; the ferries are filled with smokers. In nargile salons, patrons continue to puff away.

The tradition will not go dying lightly. Last year, a man, enraged at having his cigarettes confiscated because of the new law, shot and killed the owner of a restaurant in Saruhanli.

It all began with nargiles. Tobacco arrived from America in 1601, and thousands of nargile salons like this one sprang up in Turkey. Though the nargile itself was around long before tobacco (originating in India in the late 1500s and originally being used for more recreational substances), it became popular with tobacco’s introduction. Turks adopted the pastime with passion. Nargiles soon became important status symbols. Offering your nargile to a guest became a symbol of trust, while not providing one was a serious insult.

These pipes no longer occupy a central position in Istanbul’s social life. After the introduction of cigarettes, they disappeared almost entirely for many years. Nowadays, they are for those few who have the patience and tolerance to pursue a more balanced approach to living, for Turks who want to reach back to something valuable in their heritage, who want to become heirs to a centuries-old tradition and experience an alternative mode of time, one that contrasts greatly with the frantic chaos of modern Turkey.

But most Turks nowadays just smoke cigarettes.

I look up from writing and see a group of Western backpackers with blonde dreadlocks entering the salon. They sink into some bean bags in the corner. A waiter approaches, holding a nargile out like a giant flower, but they shoo him away. They remove their eyes from the surroundings and bury them in a guidebook. They seem to be planning the next move. “NARGILE” has been checked off the list. They snap photographs of one another from different angles and leave.

I used to be a lot like them.

But my philosophy of travel has changed a lot over these last few years, as I’ve encountered people from all walks of life, such as Göktürk, who’ve introduced me to new ways of seeing. That’s why I’ve been in Turkey for nearly a year now, just inhaling it.

I’ve always been committed to traveling somewhat slowly. I prefer to spend one month in one country rather than one week in four. I also choose to use overland transportation and only fly when absolutely necessary.

This commitment to remaining grounded comes from the longing I feel while flying. When I look down at all the earth being passed over, all the cities, and all the stories going on down there that I’m missing out on, I feel like I'm missing out on something beautiful. There is nothing beautiful about an airplane, nor how it has made the world so small.

But not many of my beginning philosophies were admirable. When I began to travel, I had the adolescent desire to visit as many countries as possible, to rack them up as though they were poker chips. I believed each country I visited somehow imparted to me its power and mystery, as though I too had in some way been engaged in the struggles of those indigenous to the land when, in truth, I had passed through them like a child through an underwater aquarium, watching whales and sharks pass over me from behind the safety of the thick glass.

I often inserted my travels into ordinary conversation to inspire admiration and respect. The more dangerous-sounding the country, the better. Using loaded words like “Colombia” or “The Middle East,” I would use the ignorance of others to implant the idea that I was courageous, never revealing the banality of time in between the emotional climaxes or the times I felt overwhelmingly lonely and afraid.

I remember an American girl in Athens one summer who rushed past me in the street wearing a fanny pack. “I can’t believe we did Greece in two hours!” she told a friend. They were already on their way back to the airport.

I contrast this way of traveling with Brianna, a girl who requested to stay with me through the hospitality network couchsurfing.org a few summers ago. She was a Louisianan who pedaled up to my home in Oklahoma one day on a bicycle loaded with luggage. She’d ridden that bike halfway across the United States and had another half before reaching California.

When she arrived at my house, she was sweaty and dirty. You could see all the country Brianna passed through in her eyes, all the fields, people, and solitude she’d known.

Passing over the Arkansas line, she’d seen a tornado reach down like a finger and scrape across the prairie a mile before it vanished into the sky.

"Threw the trees around like weeds,” she said. “I watched from an underpass in the middle of nowhere. I might have been the only one to see it.”

She had the calm about her that a forest evokes when no humans are in it. Although she’d never been outside the U.S., she knew more about the real world than anyone who’d been through fifty countries and never stopped to look at one. She sold me on the idea of traveling on a bicycle.

“You’re exposed to all the elements,” she told me. “When you’re in a car you’re in a shell. You don’t feel the weather.”

She said you get to know the land intimately; you see how slowly it changes, how the plains dry out into the desert and then slope into mountains out west. You feel that elevation rise in your hamstrings. You can stop and stare at a valley for a long time or even a particular tree if you want to. No one’s around to say otherwise. You rise with the sun and eat and sleep with the earth. You meet the backroads people, the people who’ve seldom, if ever, seen strangers. Time blows away.

Every now and again lighting illuminates the Bosphorus. Wind. Waves.

Over the past year, my mission has been to get to know the land and people of Turkey, like Brianna had gotten to know the U.S.

After my first meal, I figured I was underway. The way I saw it, the food grown in Turkey comes from the soil itself. The sun strikes a seed, and the seed pulls in water and elements from the land and, from these, builds things like pumpkins. So, when I eat Turkish pumpkins, I absorb Turkey into my bloodstream. Suppose the body renews itself every seven years, creating from newly consumed elements, which, in my case, come from Turkey. In that case, I am so far, physically, one-seventh made Asia minor. My American soil dies and is eaten by new Turkish white blood cells every day.

When I came to Turkey last February, I came to settle down indefinitely. I moved into a religiously conservative neighborhood, and it took about a month before I became a regular fixture on the street. During the first few weeks, young boys would often hound me, shouting “yabanci” (foreigner) and shooting me with cap guns, but eventually, my novelty wore off. Perhaps they accepted me.

I learned the rhythms of the neighborhood and the characters that inhabited it, like the beggar Gül. Once a week, Gül would set a bowl on the sidewalk, get on her hands and knees, and nudge the bowl forward with her nose while she pleaded for mercy. In winter, she sometimes built a fire in the middle of the sidewalk to warm her swollen, battered feet.

One day, during my first Istanbul Spring, my roommate Emre proposed I join him for a hike. At the time, I thought this meant Emre was an experienced hiker inviting me along for the ride. In reality, he had just watched “Into the Wild.” He was romanticized with the vision of trudging into the wilderness with only a backpack.

Emre is not your typical Turk. He’s a self-proclaimed “metal head,” a title he takes quite seriously. Emre spends nearly half his free time outside his desk job on heavy-metal-related activities. He listens to heavy metal music while eating breakfast.

The night I met him after I first moved into the apartment, he came home in a pressed shirt with a tie, carrying a briefcase. But then, like Clark Kent, he went into his room and transformed himself. He came out wearing all black — a Metallica T-shirt with laced-up storm-trooper boots, a nose ring, and nearly a dozen earrings in each ear. He was going out to a metal concert.

Imagine this man, well over six feet tall, appearing in my doorway one night loaded up like a donkey with brand new camping equipment, including two aluminum hiking rods he’d been feeling around the apartment with “for practice.”

We took the train across Anatolia in the dead of night and arrived at the town of Sakarya. We made our way to the home of Emre’s grandmother, Cemile, passing heaps of rubble along the way, remnants of the devastating 1999 Izmit earthquake, which had claimed up to 45,000 lives. When it happened, Emre’s family had been there, not far from the epicenter. As soon as the ground began shaking, buildings on every side of his parent’s home collapsed, leaving theirs like an up-thrust finger.

Entering Cemile’s home was like entering a rearranged memory. It could have been the home of any widowed American grandmother, with the aroma of mothballs and long-unstirred potpourri baskets. The photographs on the walls were sepia and yellowed with age. Yet, instead of the WWII Joes and Charlies of my memory, they were of Mehmets and Mustafas, strong, noble Turkish men who’d fought in the war of Independence, seated next to proud-looking, taciturn women. They stared out at me like ghosts.

Cemile’s hands looked like old, withered leaves. When Emre took hold of one, I thought it might crumble. He bowed down and kissed it, touching it to his forehead and kissing it repeatedly. She must have been over ninety.

She led us to the sitting room and held out a bottle of effervescent cologne for me. I didn’t know what she wanted me to do with it. I nearly drank it.

“No,” Emre said. “Like this.” He held his hands open while Cemile splashed the cologne over them, rubbing it into his palms and neck.

The following day, we trekked across Sakarya in a light drizzle. Emre strapped his hiking rods to his backpack and covered the gadget with a tarp, making him look like he was carrying a radio tower. We attracted attention.

“Turks don’t usually go into the wild like this,” he said, his eyes following us down the street. That’s why they’re staring.”

We hitchhiked to the small village of Doğancıl and had to walk the last half-kilometer because the road was washed out.

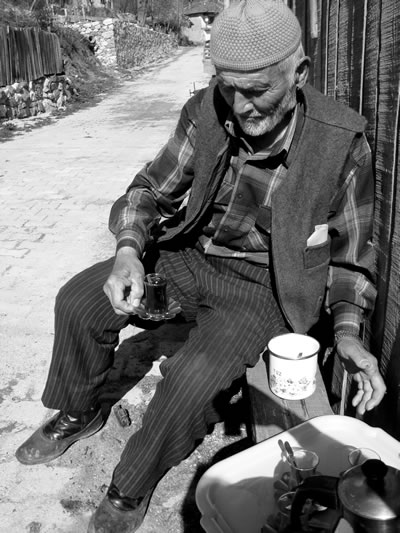

Doğancıl was a town of about a dozen houses clustered around a half-collapsed mosque. Under this mosque flowed the village water supply, a brook of sparkling water that spouted into a large tub. When I took my bottle out to refill it, an antique little man in a skull cap appeared.

“Peace be upon you,” he said in Arabic. Then, in Turkish, he said, “That’s the freshest water in all of Turkey. You could never find water like that in Istanbul.”

And then: “You’re from Istanbul, no?”

He suspected we’d come from the big city from how we were dressed. We answered yes.

“Too crowded a place for real living,” he said. “Wouldn’t live there if you paid me.”

“We’re hiking up the mountain there.” Emre pointed. “For some camping.”

“It’s quite beautiful up there,” the man assured us. He’d hiked up there many times as a youth. He said he would take us up there himself, but Emre was the village headsman these days, which meant he had responsibilities to attend to. Besides, his bones were old.

He looked towards the mountain and said: “But the weather might be too cold up there this time of year, even for you young people who own the world.”

He added that we were welcome to stay with him should we abandon our plans.

In the middle of this conversation, two women, skin wrinkled as tree bark and wearing what seemed to be clown pants, waddled up to offer us tea. They were even shorter than the older man; everyone was at most four feet. It was a town of hobbits.

The women agreed with the older man — going up the mountain would be far too cold. Besides, there could be bears or wolves. A man driving past on a tractor also stopped when he saw us. He crawled down to extend his welcome. The women informed him of our plans, and he, too, insisted we stay the night. We could all have tea together, and his wife would cook a spectacular dinner…

We finally broke away, and Emre pulled out the map. I imagined we’d be hiking for half a day before reaching a proper campsite. Still, we arrived in about an hour to a meadow where the shadow of the mountain we would be climbing the following morning stretched over us. It was a relatively diminutive mountain compared to the one Emre helped build in my mind.

I set to work constructing my tent. Emre emptied his tent onto the ground, and a gust of wind blew the flysheet into a tree. Once he retrieved it, he watched the method I was using. He was a quick learner, but it still took a while to set things up because he would drop everything every few minutes and remark how beautiful this place was.

It was his first time camping, maybe the first real-time outside of a city, and he was right. And his enthusiasm was contagious. It allowed me to see the natural world anew, with eyes of snow. When I looked over the meadow, it seemed greener and juicer than anything I could remember, with light falling over it like pineapple juice.

After lunch, we hiked around the hills and returned to build a fire when the sun was low.

Emre tried to ignite something while I gathered wood. He lit a piece of toilet paper, smooshed it under some twigs, and watched the little flame lick around for a few seconds before it vanished.

“No,” I said. “Like this.” I demonstrated how to build a teepee of kindling and then stuffed dried straw and lacerated newspaper strips inside and lit it on fire. “Then you have to give it oxygen.”

Emre tried, blowing so hard it nearly extinguished the flame.

“Gently,” I said, blowing calmly over the embers. Within a few minutes, the large branches began crackling.

We hadn’t brought anything to cook. We just wanted the heat so we could lay outside under the stars.

Emre revealed the bottle of raki he’d brought — an anise-flavored Turkish liquor. I’d tried it before and hated it, but I took some anyway and drank it straight because I wanted the warmth it provided.

“No,” he said. “Like this.” He poured some into a bottle with some stream water, making it cloud up white.

“When it’s white like this we call it lion’s milk,” he said.

The liquor sank into me smoothly. The fire danced on our faces, and the heat created a cozy little room amidst the cold winds. It was an atmosphere ripe for stories.

Emre told me stories about growing up in Istanbul and the Turkish community of Switzerland, where he’d spent a few years as a child. They were city stories as fascinating to me as they were to him: my stories about growing up in Oklahoma, going on survival campouts in the Boy Scouts, raising pigs, and the years I spent working on a ranch.

As we talked, I realized how great the divide of land and culture was between us and how insignificant that divide was. Beyond the artificial dressing heaped onto us by our societies, we were still human and connected. We were just two friends, one Muslim and one atheist, lounging by a fire in the mountains and enjoying the baser elements of being alive.

David Joshua Jennings is a writer and

photographer from Oklahoma, USA. You can find him at davidjoshuajennings.com.

|