Saffron and Nukes

Article and photos by Nancy Penrose

|

|

Imam Mosque, Esfahan, Iran

|

Introduction to Hospitality in Iran

In the heart of the “axis of evil,” I linked arms with the women students arranged around me, and we all smiled. Seven clicks later, after photographs on all the cameras, my face ached from grinning into the bright sun.

We were standing in the middle of the Vakil Bazaar in Shiraz, Iran.

Only a few moments before, I had met the eyes of a young couple, and we had nodded at each other. That was all it took. Instantly, we were in conversation.

“Kojast?” they asked, “From where?”

“Amrika, USA” I said, unsure what their reaction would be.

The young woman was wearing a chocolate-brown long-sleeved coat that reached a few inches above the knees of her black pants. Her headscarf perfectly matched the coat and framed her almond-shaped face. Her hair was completely covered.

“Amrika!” she said with surprise, then gestured to her friends browsing the shops to gather around. The group buzzed in Farsi.

“What do you think of Iran?” asked one of the other young women. She wore a print headscarf pulled back so that her black hair shone in the sun.

“I think it is beautiful, gashang,” I said. There were smiles all around.

Some spoke English, and I learned they were university students in Shiraz: one was an accounting major, another in engineering. There was an ecology major from the city of Kerman. We all had cameras. One young man, a fellow student, was designated as a photographer.

Today, I studied the photo and remembered the warmth of that moment. It was typical of the welcome and friendliness I received from Iranians in every city I visited in April of 2008. At 6 feet, I am a head taller than anyone else in the image. I, too, wear a headscarf and long sleeves and long pants. That is the law in Iran, that women shall be covered whenever in public. There are penalties — including the possibility of tickets from the morals police — for women who do not comply.

|

|

In the Vakil Bazaar, Shiraz, Iran

|

Overcoming Warnings and Fears in the Return to a Childhood Home

I had fears before traveling to Iran. The blogs, right and left, screamed of war. On March 11, about a month before I left, a U.S. News and World Report entry headline read, "6 Signs the U.S. May Be Headed for War With Iran." I skimmed the article and felt a rising panic. Then, on March 21, on a British website, there was the statement that “Dick Cheney, the U.S. vice-president, has triggered speculation that he has been using a tour of the Middle East to prepare Iran's neighbors for a possible war with Tehran.” Iran’s pursuit of a nuclear program was the cause of the tensions.

Family members were concerned for my safety. A friend who holds Israel close to his heart was disgusted that I would travel to this country whose President has denied the Holocaust. Other friends were excited and waxed poetic about the wonders of ancient Persia's history, literature, and architecture.

I was confused. I wondered if I should cancel my trip. Would I encounter hostility toward Americans? What if my own country chose to attack Iran while I was there? Would the people take out their anger on me? I am old enough to carry memories of the takeover of the American Embassy after the Islamic Revolution in 1979.

As I slept, I had nightmares about being turned away from the country at the airport in Tehran, my visa denied after all. Or worse, being taken to an interrogation room where, under bright lights, I would be questioned by men with the dark shadow of beards that signified their allegiance to the Islamic theocracy that rules Iran. After all, wasn’t I the daughter of an American man who had been part of the U.S. foreign aid machine during the era of the now-hated Shah?

Yes — and this was the point of my trip — to return to this country where I had lived 50 years ago as a young American child. I had made no secret of that fact on my visa application, and I had been approved for entry into the country.

I decided that I had to go.

As the plane from Amsterdam began its descent into Imam Khomeini International Airport in Tehran, I fiddled with my headscarf, feeling around the edges of my face to make sure that all my hair was hidden. I experimented with tucking the scarf behind my ears. I turned to an Iranian woman near me, lifting my hands into a question.

She tsk’d-tsk’d “No.” I drew the scarf over my offending ears.

“Where from?” she asked.

“USA,” I said.

She leaned close to me and whispered, “Both our Presidents are crazy.” I think it was then I knew that I’d be OK in Iran.

Exploring the Wonders of the People and Culture of Iran

I was in a famous Persian confectionary shop in Yazd, a desert oasis city. Men in white uniforms ferried great trays piled high with sweets. The shop was bright, spacious, and sparkling, full of shiny floors and shiny cellophane-wrapped gift baskets arrayed on shelves.

|

|

Old town in Yazd, Iran.

|

Bahman, our Iranian tour guide, clad in a tight black t-shirt and fashionably faded blue jeans, strode briskly to the counter, placed an order, paid for his purchase, and gestured to our little group to gather around.

In Persian culture, the guest is both king and queen. Bahman epitomized the most gracious of Persian hosts. This may be the secret to his success as a tour guide for foreigners for the past 16 years. His knowledge of his country’s history, culture, and geography is deep and wide. He has a Master’s degree in Tourism Management.

“I tried to quit tour guiding once, but I missed it so much, I went back,” he says with a shrug of helplessness. He is in his early 40s and served compulsory military service during the Iran-Iraq war. Iran paid a heavy price during this war. It began with an attack by Saddam Hussein in 1980 and lasted until 1988. At least half a million died on each side; many more fled homes in the battle zones.

Bahman is tall with curly black hair. He and his wife once worked as models. He tells how they met on a photo shoot for wedding clothes. They have a 6-year-old daughter and live in Tehran.

|

|

Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque, Esfahan, Iran.

|

He lifted the lid on the white plastic box he had just purchased and began to explain. He had bought samples of every sweet shirini, in the shop.

Pastries were shaped like small eggs, a local specialty called qottab, filled with pistachios, cardamom, and honey. There were little round balls, crisp as the desert air, that crunched into a burst of ginger and sweetness. And then there was my favorite: a soft brittle sweetened with honey, imbued with the touch of saffron, and studded with whole pistachios. Sohan is the name in Farsi. I bought a box and packed it in my suitcase like treasure.

I have always been an independent traveler; group travel has no appeal. However, getting a visa to enter Iran is more straightforward for Americans with an Iranian heritage and an Iranian family to sponsor them. Traveling with a group was my best option, my only option, really. I chose to go with Global Exchange, a human rights organization based in San Francisco, has taken groups to Iran since 2000. We were to be one of their citizen diplomacy delegations.

My hope — that the opportunity to travel in Iran would be worth the sacrifice of being locked into an itinerary led by a government-approved guide — turned out to be the same hope held by everyone else in our delegation. We were a band of nine independent world travelers forged by necessity into a group, and we all felt lucky to be able to make this trip.

Shiraz is the city of roses, wine, nightingales, and poets. The wine, like all alcohol, is banned under the laws of the Islamic Republic. However, the roses are still as fragrant and the nightingales as musical as they were 700 years ago when the great Persian poet Hafez captured them in his verses.

|

|

At a teahouse in Shiraz.

|

On a Friday, one of the days of the Muslim weekend, we joined the crowds of Iranians strolling the pathways among the roses at the Aramgh-e Hafez, the poet’s tomb.

Hafez was brought alive for me as a young woman stood at the head of his marble sarcophagus and read a poem aloud to an appreciative crowd that had gathered around. She wore a purple coat. A daring red blouse peeped out from the neckline. Her long black scarf, one end tossed over her shoulder, was set far enough back to reveal an abundance of curly black hair. She held a fat book, fingers poised, ready to turn the page. I did not understand the Farsi, but I took in Hafez's anguish, drama, and passion that rose and fell in her voice.

In one of my favorite poems, the poet writes:

I

Have

Learned

So much

That I can no longer

Call

Myself

A Christian, a Hindu, a Muslim

A Buddhist, a Jew

The Truth has shared so much of Itself

With me

That I can no longer call myself

A man, a woman, an angel,

Or even pure

Soul.

Love has

Befriended Hafez so completely

It has turned to ash

And freed

Me

Of every concept and image

My mind has ever known.

Another Perspective on Freedom

Each day in Iran, I found freedom from concepts and images I had known.

We met with Grand Ayatollah Emami in Esfahan, a gracious river city of ancient bridges, blue-tiled mosques, and verdant gardens. There are only about 50 Grand Ayatollahs in Iran; it is the highest of the clerical ranks in Shiite Islam. Emami is a liberal. He has his own satellite broadcast station, Salaam TV, to reach his followers in the U.S. and Europe. A sweet-faced man of 73 with a flowing white beard, black turban, and brown cloak, he settled into a chair with the help of his cane. We were in his private residence, in the courtyard, under the shelter of the leaves of a grape arbor that dappled us with shade.

|

|

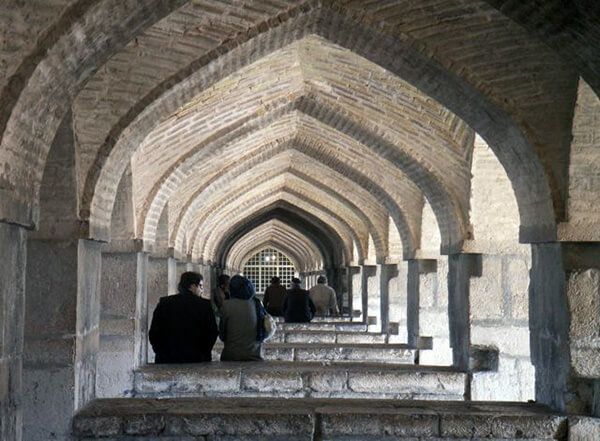

Lower level of Khaju Bridge, Esfahan, Iran.

|

The Grand Ayatollah invited our questions. Bahman translated as Emami answered softly with the simple wisdom of a spiritual leader.

When I asked him what message he would like to send the American people, he replied: “Please tell your fellow people to think more and study more rather than being bombarded by the mass media. The best way is to go looking for the truth, find the truth yourself rather than listening to the mass media.”

On Girls and Women in Iran

In Tehran, our group was invited to visit Roshangar High School, a high-ranking conservative school for girls run by an Islamic foundation. Bahman reminded us that it would be haram, forbidden, for the women in our group to shake hands with any men we met.

Roshangar has a high rate of acceptance into Iranian universities, which are co-educational. We were told that women hold 62% of the places. This did not surprise me. I had seen and met women active in many facets of Iranian life: driving cars, moderating television programs, working as tour guides, teachers, principals, doctors, and industrial project managers.

And all these women were wearing some form of hejab, the modest dress required by law. The conservative Islamic ideal in Iran is hair wholly covered, body shape concealed, and only hands, face, and feet showing. But each woman chooses how far to push — or not — the limits of the law. I saw hair-covered and frosted hair frothing out from beneath the front edges of headscarves. I saw conservative women in the long black tent of a chador. I saw many other women wearing pants beneath the knee-length coat known as a manteau. The most daring was the one who had rolled her sleeves to her elbows. Yet whatever they wore, they did it with a flare and grace that I, a Western woman, felt unable to attain.

We were the first American group ever to visit Roshangar. We were welcomed into a cheerful room where student-made posters in bright blues and reds hung on the walls. We were invited to take seats at a table. At each of our places was a cup of tea, a bottle of water, and a plate on which a cucumber, apple, orange, and banana were artfully arranged. A covered glass bowl held cubes of sugar. Bouquets of roses in crystal vases perfumed the air. There were plates of pistachio nougat candy and cookies studded with almonds and raisins. We were the honored guests. We were being received in the Persian style.

We were given a tour of the school, which has an all-female faculty. The buildings are constructed so that the students may attend classes without wearing a hejab if there are no men. But on the day of our visit, because of the men with us, the teachers and students were all clad in black chadors. In the computer lab, the girls turned from their monitors to greet us, their faces smiling ovals framed in black. The teacher proudly pointed out the new server.

Leaving the men behind, we women followed the flow of the vice-principals chador into the gymnasium, just one part of a sports complex that includes an Olympic-size swimming pool. The gym was filled with the humid smell of exertion. Feet pounded up and down the varnished wood of the basketball court. The shouts of young women cut against the twang of bouncing basketballs and the smack of palms on volleyballs. Bare legs, flying hair, faces that glowed with the joy of the game and the competition.

We foreign women pulled off our headscarves and ruffled our hair. A joyous release. A group of girls careened around a basketball and gestured to me to join them. I plunged in. My long, loose shirt and baggy pants flapped as I bounced the ball they passed. I paused, threw, and made a shot that swished through the basket. Time for only a few cheers before my group was racing off to the other end of the court. I let them go and stepped back onto the sidelines.

The coach, a 30-something woman with auburn hair and wearing a T-shirt and shorts, blew her whistle. The girls froze. The coach shouted something in Farsi. There was a scramble to the bleachers, where piles of chadors dotted the seats. Instantly, all the girls were covered and safely draped as the men from our group entered the gym. I pulled up my headscarf once again.

The Richness, Mystery, and Truth of Natanz

Natanz is a pretty town known for its walnuts, pears, grapes, and saffron. It sits in the mountains some 100 miles northeast of Esfahan. Our big orange bus barely fit through the tree-lined streets that opened onto the main square. We visited a mosque built in the early 1300s and had tea under the shade of a tree. Then we went in search of natural treasure. Bahman led us to a shop where we bought the dried filaments of Crocus sativus. Saffron. Red gold. Harvested by hand from purple flowers. By weight, it is the world’s most expensive spice. A hallmark of Persian cuisine.

Natanz is saffron, but Natanz is also nukes. Less than an hour north of the town lies one of Iran’s nuclear sites that so concerns the world. Is Iran developing nuclear technology for peaceful purposes only? It all depends on who is talking and who is listening.

As our bus hurtled north along the highway outside Natanz, Bahman told us to keep our cameras packed away. As we drove by the facility, I scooted to a seat on the left side for a better view. The day was gray with a haze that stretched from ground to sky. The mountains loomed desert brown. Behind a high barbed-wire fence anchored by lookout towers, I made out the shapes of tanks. They were topped with anti-aircraft guns aimed at the sky.

At that moment, I wondered: were the eyes of cameras, satellites, and soldiers paid for with my tax dollars, watching our bus hurtle down the highway? Were there missiles being readied for launch from U.S. Navy vessels stationed in the Persian Gulf, their target the huddle of buildings in the distance beyond the fence?

The gray haze remained unchanged. We continued toward Tehran.

I got a second look at the Natanz nuclear site a few days later when I was home again and reading back issues of the New York Times. “A Tantalizing Look at Iran’s Nuclear Program” was the headline. “… President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad visited the desert site, and Iran released 48 photographs of the tour, providing the first significant look inside the atomic riddle.”

One analyst said, “This is intel to die for.”

I went to Iran to reconnect with a place I had lived as a child, and I occasionally met up with the little girl from the 1950s. The smells and tastes of food struck the gongs of memory: the fragrant steam off a platter of rice, the chewy smokiness of flatbread fresh from the oven, and the salty-sour bite of a pickled green plum that had been forbidden to me as a child but that I had eaten anyway.

But I returned home with more than rekindled memories. I carried back stories from the 21st century, my own kind of “intel,” a heart-knowledge that has taken me beyond the narrow dimensions of headlines. I was there for only two weeks, but as Hafez might have said, the truth of Iran shared much of itself with me.

|

|

Schoolgirls on field trip, Chehel Sotun Palace, Esfahan, Iran.

|

Nancy Penrose lives in Seattle. She is a lifelong traveler who writes to explore the territories where cultures converge. Her essay about Laos, "The Warp of Memory," was the Grand Prize winner in the Summer 2008 issue of Memoir (and). Her story set in Spain, "Flamenco Form," won the Grand Prize Silver Award in the First Annual Solas Awards.

|