Dangerous Love in India

Article and photos by Lucinda Tikwart

"Riots in Agra!” screams the smudged headline of a newspaper that’s bleeding onto the fingers of a turbaned man next to me. We are a dot in the middle of the map of India, where we take turns pacing the mosquito-infested moonlit train platform. The families around us have packed away their cooking pots and stretched out in sleep on the warm ground. Our uncomplicated journey has morphed into two full days of schizophrenic travel, and we have been at this station for nine hours. Our itinerary has been disturbed by bloody clashes with Gujjar protestors seeking reclassification under the caste system. We don’t fully know the dangers of this latest riot.

However, the backpacker grapevine tells tales of blocked highways, trains derailed by piled bodies, rotting food, and burning tires. The mustached conductor on a passing train could not tell us what trains to expect. The stationmaster, who promised to look after us, is prone on his counter. So we are heading in an altogether different direction, weaving our way to the little town of Amritsar to experience first-hand the famously charged Pakistani border-closing ceremony. I cannot put this on any of my scrawled postcards mailed to neat apartments on perfect streets back home. Instead, I describe how we have immersed ourselves in the chaos and are lapping up the raw beauty distilled around us, hungry and enthralled.

“You two, an arranged marriage or love marriage?” We have been asked this question countless times during our travels in India. This time it is the turbaned man on the neighboring bench. We smile back in answer.

My new husband and I are healing our marriage. What his grueling banking job hours stole from us in our year of engagement as I planned a wedding alone, it replaced with one mutual goal. While other newlyweds were baby-proofing their homes, we stored wedding gifts. Knee-deep in backpacks, we raised the eyebrows of impatient relatives as we schemed 95 days of togetherness. We were determined to step out of our world and into another, to find ourselves as a “we,” traveling through Asia. This decision was even less welcome to others after the week’s earthquake in China, a deathly storm in Burma, and violent Tibetan crackdowns after the most headline-grabbing protests in two decades. There was, of course, also Nepal, enduring the dethroning and abolishment of a 240-year-old monarchy, and Jaipur, licking her wounds after a recent terrorist bombing. But the absolute risk lay in something foreign to us both: undiluted time together. A make it or break it a dangerous journey. Armed with nothing but a hastily scribbled “10 Agreements of Travel” we had crafted at San Francisco International, promising never to make an important decision when hungry or tired and to ask for “time outs” when needed, we set out to find each other again.

“Love,” I reply. Definitely love.

We have already fallen in love with each other anew and with India. To try to distill this mammoth country into one sense is brave. “India smells like fire,” I try, and Alan roars with laughter. “It does, it does,” he says, with sparkling eyes I had not seen brighten for far too long. It’s that same laugh I hear from him when there are cheeky whoops of “Paki!” called out in mock bravado from behind tea stalls we pass. He must shave that beard tomorrow, I remind myself. We are going to wake too close to Pakistan to encourage confusion and ignite historic anger.

“You know, my cousin has four children already.” It’s the man across the way. Again, it's the same challenge. We know we should be making babies. In India, this trip, we are told, is called a “babymoon.” “How old is your cousin?” I ask politely. “Oh…he’s 19,” he replies, smiling. And his wife?” asks Alan, joining us. “She just had her 15th birthday,” he smiles back.

In the scorching heat of night, I unstick my arm from the plastic bench seat and slide it gently through Alan’s, just a little tighter. Traveling here is not for the faint-hearted; we are reminded as we watch an eerily silent, passing coal train as long as a football field rushes a bleating goat off the tracks. A food vendor chops onions silently on the stained floor as the geckos chase each other madly along the walls. Off in the distance, I can hear the clicking of a cycle rickshaw through the sleeping streets.

We jolt to the hiss of the last passenger train of the night drawing in, and Alan and I tug our backpacks on quickly, not knowing what will happen once we board. The conductor warned us that it was as complete as the others and barred our path to the air-conditioned cars.

This will be our first time braving the general reservation class. We have heard the stories of “cattle class,” as we have heard it called, and seen people in the movies hanging off the roof. It’s already darkened when we enter the train, and we apologetically sidestep sleeping bodies on the floor between rocking carriages. Clumsily, we weave deeper through the silent carriages, seeking a spot to sit. The air from the open windows is breathless and unforgiving. It’s the hour before the sky cracks itself open with lava light, and I hesitate, burning the moment into memory. We are fighting exhaustion from our long day, and I am avoiding the unnerving starter blocks of the train toilet. Floor to ceiling, there are sleeping bodies comfortably stretched out in layers of humanity. We swerve the swollen bare feet sticking out of bunks, only to crush into hot, sleeping faces. My overly complicated Western manners don’t translate well into this simple way of life we are bumbling into.

In an explosion, Alan knocks an overhead light bulb with his gigantic backpack, scattering the shards of glass down his shirt. I work to shake loose the glass trapped against his skin. We are making mistakes in our weariness.

The deeper we journey through the blackened carriages, the more desperate we feel. There is a person filling every nook and cranny, and extended families languidly stretch across one another.

At this moment, I can only close my eyes and bite back a defeated wail. Balancing the weight of our backpacks against the wall, we wait to escape at a station that never arrives. Standing at the door to the overflowing toilet, we look at one another sorrowfully. “I’m sorry,” Alan’s defeated voice quivers. “I let you down. I got us into this. I don’t know what to do,” he says with a defeated look. I am more tired than I can ever remember. India has been a series of twists and turns that have been delightful but also testing.

Then I feel a tap on my shoulder. “Come,” beckons a man with the map of his life on his face and sweat stains on his shirt, gesturing towards his bunk. “You sit. We share,” he explains. “Shukriyaa,” I say weakly.

So we both sit. Listening to the train's breathing, I am quietened by the stranger’s kind gesture. Alan peers around the bend and mouths, “I love you.” All I can think of is who will save my husband from standing in the reeking urinals with his pack on all night.

Our train journeys through the muggy night, heading north. As the untouched dawn breaks, bodies rise. Rubbing their sleep-filled eyes, they make their wobbly way to one tiny communal sink to complete their rigorous cleansing ritual. Alan sneaks up a ladder to claim an empty bunk under the ceiling, where he passes out.

The women loll on bunks, exposing voluptuousness under a jewelry box of saris, and stroke their faces with talc. Their coal-black hair cascades down arched backs as they swat at clambering children. They are devastatingly beautiful, and I can’t stop myself from staring at their toasted skin, hypnotized by clinking bangles.

But to the passengers on our train, we are the show, and they look upon us the whole ride. I am used to this now and have learned to only steal affection from my husband when we are in the shadows. Surprisingly, as tourists in India, we have felt very alone.

With a sudden crowd rustling, hustlers break onto the floor before the show starts. To my surprise, it's two small boys who cannot be more than four years old. One has a drum. The second only has attitude, which he displays as he starts this funny little jig through the rows to his brother’s beat. He bobs his head, causing the torpedo tied to his hat to spin circularly. I suppress a delighted giggle as he rolls his little pelvis, hands on hips…all with a straight face onto which a giant black comical mustache has been painted. He somersaults his way down the urine-drenched floor and then climbs back and forth through a tiny metal hoop. I am truly mesmerized. Giving what I can, I wave him off with “mujhe maaf kar do,” but he forgives me by kissing my feet, hands, and stomach.

|

We turn to the food sellers' calls as they announce their wares. Seasoned cucumbers are eaten whole, alongside dry noodles, spicy samosas, and fresh, pulpy mango juice. The women around us break open baskets of fleshy naan, palak paneer, parathas, and atjar which fill the train car with cardamom and cloves. “Come, come. Enjoy!” they chorus, graciously preparing us heaped plates. And we do while they grill us on our story. The sweet coconut in their homemade burfi is sinfully delicious. I gorge on great hunks while they stuff the leftover tin into a zipper in my pack. We, in turn, photograph their hennaed hands and kohl-eyed babies, trying our hand at Hindi phrases that sound as if we’re talking with a bite of raw potato in our mouths.

|

The adolescent sun quietly simmers, promising blistering temperatures by noon. Alan’s watch tells us it's 38 degrees Celsius, and you could already fry a cat on the roof, but never mind an egg. No one seems to notice the searing temperature or the flies that outnumber us. We smile away sweat with rivulets trickling down our backs.

All of a sudden, a charge fills the air. The sky is a swirling, darkening, meringue mix, switching faster than a bruise to a seething, angry black. The wind whips the trees, and whirls of dry sand are whisked into the air alongside lightning flashes and grumblings. A proper pre-monsoon dust storm is upon us. It is ferocious, shaking our little train in fury, immediately coating all surfaces in a film of sand. I am blinded with dust and feel it creasing my palms and nails. The women slam the shutters quickly, but the Gods are angry, and we cannot close our windows fast enough. Everyone looks around, sharing relief and dusting one another’s hair and ears.

It is not long before the hot rain follows. This time, we fling open the shutters and turn our faces to the sky, licking the fat drops that hit our cheeks. “Hot chai! Hot chai!” It’s the return of the vendors. Hopefully, they will make their way through the car. “Dusty chai!” retorts my cheeky husband, with a survivor’s recklessness, and everybody laughs, showing betelnut-blackened gums.

The train stops, and as a mass of soaked bodies, we squeeze together tightly, all heading for the same door. The porters hurry past the opening with mountains of suitcases on their heads, leading travelers to first-class cabins. They dart in and out of the confusion. We stumble out the door, past the proud turbaned servers of first class, our eyes trained on the red-jacketed porters ahead. They move quickly, hoping to deliver their customers to the correct seat and earn their reward before hopping off and to safety from the departing train gaining speed. I remember something a passing traveler shared the night before: “India is like a Picasso. Everything is there. It’s just in different places.”

The disappearing sign on the wall tells us we have arrived at our destination. “What are you looking for?” demands a tout from our welcome brigade as we step out of the station into the burning sun. “Nothing!” is my trained response, waving him off. “Nothing is there,” he says, pointing to the road leading out of the station and into town.

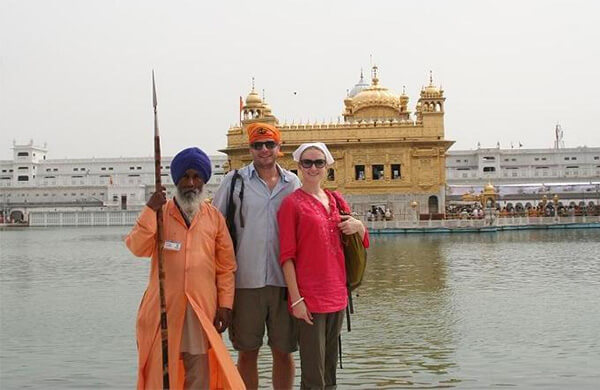

In Amritsar, the streets have no names, and finding our way around the frenetic alleys is like a game show in which the host doesn’t know the answers. We carefully make our way hand-in-hand down the maze of winding streets, looking up at the minarets while elbowing each other for a better view of the moving traffic below, which engulfs us like tidal waves. A monkey on a leash is pulled behind a stalled cow, eyeing a woman hunched over her cooking pots in the dirt. The din is constant, and our senses are assaulted. Blinded by the scorching sun, the glitter of the Golden Temple, a dome caked in 750 kilograms of pure gold, draws us in. Here, the gold-plated gurdwara — Sikhism’s holiest shrine — attracts up to 40,000 pilgrims daily.

|

Shrunken older men leaning heavily on masts, young children with brows to the toasted slabs, and everyone in between de-robe and wade into the jade holy water at the feet of the dome. They tip water over their glistening heads, deep in prayer, and the air is filled with soothing, hypnotic chants. We step aside to allow passage to the moving, muttering group washing the milky egg-white marble floors meticulously with passed buckets. “The air is on fire,” I say in wonder at the blinding warmth as we stare in chorus at the luminosity of a scene of vibrancy filling the spaces between life and death. My skin opens up, drinking in the light. At the same time, Alan reads out loud about then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, who paid with her life for Operation Blue Star, which left thousands dead at this site in 1984. Today, the scars are healing, and we feel part of something beautiful.

Frenzy at the Border of India and Pakistan

We exit the shrine and find a driver at the gates, whose name we never know but who agrees to take us to the Wagah gate on the border. He borrows a small hurtling vehicle without seatbelts. We clench our teeth and share terrified half-smiles as he speeds along. We are reminded of the skills of the Indian driver as he chaotically swerves between painted faces of decorated freight trucks pregnant with a bounty of tomatoes from the fertile Punjab region. Until last year, these truck drivers relied on 1,000 porters to carry produce on their backs across the no man’s land that divides Pakistan and India. We feel naive and stupidly reckless in our decision as he veers across both sides of the road, honking manically to the beat of a blinding sun.

Arriving just in time for the ceremony, we join the trailing crowds as they enter the arena. We note the popcorn stands at the entrance — alongside sliced coconut and pineapple juice — incredulously. The stage and stands in front of the gates to Pakistan are already full of expectant faces. We feel small and crushed until we are plucked from the seething mass of butterfly saris by a guard and ushered into a safety net for tourists and officials. Young Indian girls methodically work themselves into a frenzy, dancing in circles below us with total abandon. At the same time, a master of ceremonies flares the seeping masses with “Long live Hindustan!” The stands are a kaleidoscope of saris in scarlet, saffron, emerald, and gold. Streamed obscenities blend with patriotic chants from both sides of the border. At the same time, the blaring of dance music reaches a fever pitch. We feel enveloped in an international war of dance and song. Scowling guards — in gorgeously decadent uniforms — take turns parading to the gate while flicking their head-combs across at Pakistani brethren in anger. They kick heels in the air, charging past the cheering crowds, gesturing angrily. No one wants to lower their flag first on this painstaking diplomatic stage, so the act is drawn out with much flinging open and slamming of gates on both sides. And then, suddenly, as seamless as the dropping of the black velvet curtain of night, the flags are folded away, bugles dropped, and the guards turn to the roaring audience, like stars on a stage, smiling as they hand out refreshments. The border is closed, and the lowering of the flag between the two hostile nations is over for today.

|

|

It is only racing back, overtaking lopsided rickshaws crammed with families, that I suck in the warm air with relief, feeling a sudden overwhelming tiredness. Alan leans across to envelop my hand into his, and I smile back, still slightly drunk with our dare. I settle into his shoulder, close my eyes against the scenery's blur, and breathe in India. It’s been a long day of riots and a train story we can share with our children one day. Flirting with danger is my luxury on this expedition. Regardless, many living on this rich soil will wake to a tomorrow whose genuine risks will replay themselves with vigor and strength, like the performance at the border. My job as their witness is to share my India with the world and, in exchange, accept her gift of renewed love.

Growing up in South Africa, Lucinda Tikwart learned to get high by seeing the world. She got her first taste of travel as a small child in the back of the family car on annual road trips through Southern Africa, graduated to backpacking through Europe alone before she was 18, and only this year celebrated her new marriage by setting out to explore Asia for three months with her husband. Together, they have settled permanently in San Francisco, California, where she quit her successful executive marketing career this year to focus on freelance writing.

|