Mother Africa in Brazil is Alive and Well

Exploring Afro-Brazilian Culture in Northeastern Brazil

by Volker Poelzl

|

|

Maracatu is a theatrical dance popular during carnival in Recife.

|

Northeastern Brazil prides itself on its unique cultural heritage, especially its Afro-Brazilian traditions. Brazil's African heritage goes back to colonial times when the Portuguese — who were the first Europeans to settle in Brazil — brought several million enslaved Africans to Brazil to work on plantations. Despite repression and restrictions, people in Brazil who were enslaved succeeded in preserving much of their African cultural traditions, many of which are still practiced today. Visiting Northeastern Brazil is a feast for the senses. Streets are filled with the smell of spicy dishes sold by women dressed in colorful costumes. You can hear fast percussion rhythms coming from rehearsal halls or performed by street musicians, and you can watch captivating street performances of Brazilian martial arts.

|

|

Salvador's Pelorinho district is a popular gathering spot at night.

|

The Northeastern state of Bahia has the highest percentage of Brazilians of African descent. No matter where you go, you will find lively expressions of cultural traditions of African origin. The state's capital, Salvador, is Brazil's center of Afro-Brazilian culture, and there are cultural events, parades, exhibits, concerts, and performances all year round. During a short visit, Salvador is a great destination to taste Brazil's rich African heritage. Yet, because of its popularity with Brazilian and international tourists, Salvador's display of Afro-Brazilian culture has lost some of its authenticity and has become widely commercialized. It is a good idea for tourists in the city's historic Pelorinho district to go beyond these cultural events, escape Salvador, and visit some of the smaller surrounding towns. If you have more time, consider visiting other states in the Northeast with a robust Afro-Brazilian influence, such as Pernambuco (with its capital, Recife) and Sergipe.

A Potpourri of Cultural Traditions

in Northeastern Brazil

African cultural influences infuse every aspect of public and private life in northeastern Brazil. From religious worship to music, dance, food, and language, Brazilians of African descent have left an indelible and lasting imprint on regional culture.

Candomblé

in Northeastern Brazil

Candomblé is faith-based on the West African traditions of the Bantu and Yoruba people. Followers of Candomblé believe in the Supreme Being Olorum, the creator of the cosmos, and spirits known as orixás (pronounced: Oh-ri-SHAHS). Candomblé is widespread among the black population of Brazil's Northeast, mainly in Bahia, Sergipe, and Pernambuco. The Candomblé ceremony is a complex feast involving sacred dishes, dances, drumming, and sacrificial rites. Candomblé rituals aim to establish contact with the orixás, who can help in case of illness and other needs. The spirits enter the bodies of the believers, who then fall into a trance. The ceremonies are held at Terreiros, where the Candomblé places of worship are known. Many candomblé congregations admit visitors, but in Salvador, many ceremonies are held for paying visitors. You will have a more authentic experience of Candomblé in smaller towns near Salvador around the enormous Bay of All Saints, a region known as the Recôncavo. Cachoeira is a regional center of Candomblé with many popular festivals. Still, Afro-Brazilian culture is also vital in the towns of Santo Amaro and São Félix.

Capoeira

in Northeastern Brazil

Capoeira is a Brazilian martial art form developed by run-away enslaved people to defend themselves against the mercenaries sent out to capture them. In its contemporary form, Capoeira is a stylized dance/fight performed by a group of fighters (capoeiristas) who form a large circle with the audience. The musical element of Capoeira consists of instruments of African origin, such as the berimbau (a 1-stringed instrument made from a gourd) and several percussion instruments. The capoeiristas move to the rhythm of the music in a characteristic step and execute a series of complex acrobatic movements such as somersaults, cartwheels, and handstands. During the simulated fight, the opponents never touch but attempt to outdo each other using speed and acrobatic skills. After a few minutes of simulated fighting, a new pair of dancers enters the circle and continues the skill demonstration. Capoeira is performed in public by capoeira schools all over Northeastern Brazil.

|

|

Capoeira is a fight dance first developed by escaped enslaved people as self-defense. |

Carnival

in Northeastern Brazil

Although Brazil's Carnival is a Catholic tradition, Afro-Brazilian carnival groups, known as Afro-blocos, play an important role all over Northeastern Brazil, especially in Salvador. Among the most traditional groups in Salvador are Ilê Aiyê, Ara Ketu, and Olodum, known for their colorful costumes and fast percussion beat. The parades of Afoxés (carnival groups associated with Candomblé) also form an integral part of the Carnival in Salvador. They parade through the streets and sing to a fast percussion beat in African languages. Among the oldest and best known Afoxés is Filhos de Ghandy (The Sons of Ghandi), whose members wear blue and white costumes and white turbans.

Music and Dance

in Northeastern Brazil

Afro-blocos such as Ilê Aiyê, Ara Ketu, Olodum, and Afoxés such as Filhos de Ghandy have been critical in preserving and expanding Afro-Brazilian musical traditions. Olodum is best known for fusing Afro-Brazilian rhythms with musical styles from the Caribbean, a musical style known as "Samba Reggae." Olodum has also gained international fame since it participated in recordings by Paul Simon and Michael Jackson. On the other hand, Afoxés such as Filhos de Ghandy remain primarily faithful to "ijexá," the traditional rhythm and music of Candomblé ceremonies. When visiting Northeastern Brazil, you can expect to hear traditional Afro-Brazilian rhythms and new experimental music that combines various musical traditions from Brazil and elsewhere.

Many of Brazil's famous musicians and songwriters, such as Dorival Caymmi, Caetano Veloso, Gilberto Gil, Gal Costa, Maria Bethânia, Daniela Mercury, and Carlinhos Brown, are from the Northeast. Their music often includes musical and rhythmic elements of the region's rich African heritage. Many of Brazil's most popular songs of the past century also pay tribute to Brazil's African heritage. There are songs about popular dishes of African origin, colorfully dressed women from the state of Bahia, the struggle of black Brazilians for equality, influential personalities of Afro-Brazilian descent, as well as ballads and tributes to the many orixás (spirits), ceremonies, and festivals of the candomblé religion.

Dances are a very popular folkloric tradition in Northeastern Brazil, and there are dozens of folk dances performed by cultural organizations during Carnival and other festivals. Among the most popular dances are the coco, a fast-faced that imitates the movement of opening a coconut, and the lundu, a circle dance of African origin. The best way to watch a performance of these Northeastern folk dances is to attend a rehearsal or performance of the Balé Folclorico da Bahia, a professional folk dance group in Salvador.

The state of Pernambuco, especially the city of Recife, has its own unique dances of African origin, most notably the Frevo, a fast-paced dance derived from capoeira steps. Another popular tradition in Pernambuco is Maracatu, a theatrical dance performance especially popular during the Carnival. The dance is performed by organized groups called Nações de Maracatu, or Maracatu Nations, mainly consisting of Afro-Brazilian members. The performance centers on the character of the "King of Congo," who parade through the streets in colorful costumes with his queen and the court while dancing to a fast percussion rhythm.

|

|

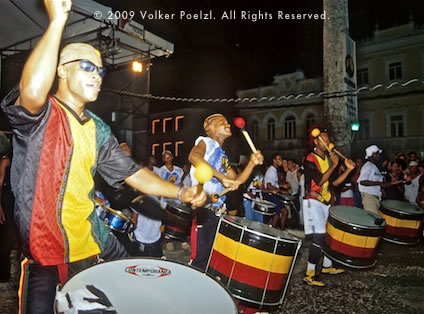

Olodum is a popular Afro-Brazilian cultural organization in Salvador that regularly performs publicly.

|

Food

in Northeastern Brazil

Northeastern Brazil has a rich culinary tradition of African origins. No matter where you travel, you will find food stalls on the streets offering a variety of local favorites. Food safety can be a concern when eating on the street, and it's best to eat at a food stall with a high turnover to ensure the food is fresh. Many restaurants serve typical regional dishes, and if you don't feel like eating on the street, find a nice local restaurant specializing in regional cuisine.

One of the main ingredients of local dishes of African origin is dendê oil, a robust orange-colored oil made from the fruit of a palm tree brought to Brazil by enslaved Africans. Among the best-known dishes is Vatapá, a purée made from dried shrimp, ground peanuts, cashews, coconut milk, and dendê oil. Moqueca is a seasoned stew with coconut milk and dendê oil. It is prepared with fish, shrimp, or other seafood. Ximxim de galinha is a casserole with chicken pieces cooked in a sauce of ground peanuts, cashews, ginger, dendê oil, and dried shrimp. It is usually served with farofa (roasted manioc meal). Bobó de camarão is a purée of dried shrimp, coconut milk, manioc meal, dendê oil, and seasonings mixed with fresh shrimp. Acarajé is a popular appetizer sold at food stalls all over Bahia. It is a round ball of bean batter deep-fried in dendê oil and filled with Vatapá purée, hot sauce, and dried shrimp.

Handicrafts

No matter where you travel in Northeastern Brazil, markets, shops, and cultural centers sell traditional handicrafts. You will find woodcarvings of saints and Candomblé spirits, ceramics, basketry, hammocks, and a wide variety of amulets, adornments, and accessories used by followers of Candomblé. One of the most ubiquitous items is the figa, a good luck charm carved from wood in the shape of a clenched fist. Consider you'd like to learn about typical Afro-Brazilian handicrafts before shopping. In that case, you should visit the Museu Afrobrasileiro — the Afro-Brazilian Museum in Salvador — which displays typical local handicrafts. Salvador's historic Pelorinho district has a lot of shops that sell local handicrafts, and so do local markets, such as the large two-story Mercado Modelo by the waterfront in the lower city. But imagine you would like to support local artisans as opposed to merchants. Visiting the Visconde de Mauá Handicraft Institute (Instituto de Artesanato Visconde de Mauá). This government-funded organization trains and promotes local artisans and also sells their work.

When to Go

to Northeastern Brazil

December through March (the Brazilian summer) is the most popular time for Brazilians to travel, especially during the two weeks leading up to Carnival. During this period, the largest and most lavish parades and festivals occur, while prices are high and hotels are booked. Assume you would like to experience carnival activities, parades, and concerts without the large crowds and high prices. In that case, you might want to consider traveling around the Northeast starting a month before Carnival, when the "pre-carnival" celebration takes place. In Salvador, you can experience Afro-Brazilian culture, which includes lively street festivals and performances year-round. Starting around June, Afroblocos and Afoxés in Salvador will begin rehearsing for next year's carnival celebration. Ask the local tourist office what rehearsals are open to the public.

Festivals

Many famous festivals in Brazil are associated with the deities of Candomblé. Among the most popular celebrations of Candomblé is the Festa de Iemanjá, or the "festival of Iemanjá," dedicated to the goddess of the sea. The festival is celebrated in Salvador and elsewhere on February 2, accompanied by processions, such as music and dancing.

The Lavagem do Bonfim, or the "washing of Bonfim," is the most popular Candomblé festival in Salvador and takes place on the second Thursday in January. It is a long procession through the city, accompanied by food, music, and dance. The celebration ends with the symbolic washing of the steps before the church of Nosso Senhor do Bonfim (Our Lord of the Happy Ending).

Northeastern Brazil

Resources

Balé Folclórico da Bahia

Brazil's only professional folk dance company focuses on folk dances — mostly of Afro-Brazilian origin. Their weekly rehearsals in Salvador's Pelorinho district are open to the public.

Museu Afro-Brasileiro (Afro-Brazilian Museum) in Salvador presents exhibits of Afro-Brazilian artifacts, from pottery and woodcarvings to Candomblé costumes. Make sure you look at the carved wooden reliefs by Argentinean expatriate artist Carybé, which depict the orixás (spirits) of the Candomblé religion. Terreiro de Jesus, Pelourinho, Salvador.

Candomblé Temples (terreiros)

If you visit a terreiro outside the city center, it is best to take a taxi. Many terreiros are located in poor neighborhoods and are often difficult to find. Some guides take tourists to Candomblé ceremonies for a fee, but many ceremonies are performed for tourists and lack authenticity. Visitors at authentic ceremonies are not charged a fee but may be asked to donate. If you visit a Candomblé ceremony, make sure you wear decent clothing and do not wear black colors. You are not allowed to take pictures or film during the ceremony.

|

Volker Poelzl has lived in Brazil for several years and has traveled extensively throughout the country, including Northeastern Brazil. He is the author of "Culture Shock! Brazil”.

|