Taking Long Lunches in France

Article and photos by

Kate Hunter

|

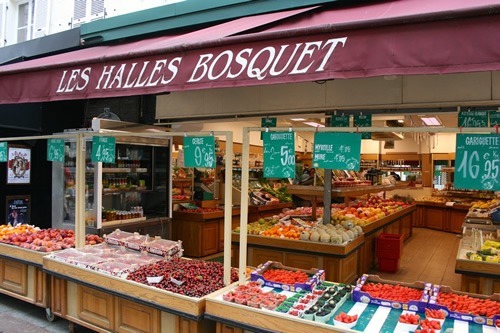

| One of many lunch options

in France, where food is enjoyed slowly. |

I was a New Yorker. It was normal

to sit in close quarters with colleagues at work during lunch

hour and discreetly consume a mixed salad that I bought

at the café that was a part of the

lobby within the office building. I thought it was standard to rush to work and

then sit for the first hour reading the news. I thought

all of this was normal until one birthday I arrived at

my desk only to see a piece of cake left for me on my

chair, while my colleagues sat fixated at their computers. I

worked in a tense and awkward environment, with my coworkers

too within their bubbles to lift their eyes for a moment

and even wish me happy birthday. In that moment, I wondered

if I would ever find a place that would pause to celebrate

life.

Transitions

I moved to a historic town

20 kilometers (12 miles) west of Paris, France. At first,

stereotypes about the French were in the forefront of

my mind, I experienced culture shock,

and even moments of tears. Only after living in the country

for some time did I start to see the wide array of cultural

colors shine though.

When I arrived in France, I did not

speak any French. I would spend days dedicated to French

lessons and working at an international school in the

afternoons. In between, I would struggle with the metro

system, walk endlessly, only to make it home to inhale

lunch. I would turn around quickly to bike to the office,

all so that my school-lunch-work commute would take up

less than an hour.

My boyfriend, now my époux (husband), would

laugh and say, “No one is checking, chill out, relax

a few minutes…” Out of personal habit, I thought that

I was being a responsible and diligent person. Anyway,

how could I deserve an extra few minutes when everyone

else must be expecting me back at work?

Learning to Work to Live

The same personal habits and attitude

started to come to my attention when I would collaborate

with my French colleagues, whom I accidentally offended

on a regular basis with butchered and politically incorrect

French phraseology. Only through hearing rumors did I

realize that what I thought was an honorable work

ethic on my part was so intense that they actually thought

I was working to get them fired or steal their jobs.

I felt that my coworkers did not understand that I just

wanted to help and do the most I possibly could. In France,

my behavior could be interpreted as a threat, while in

New York it would have been positively reinforced.

In New York City, you do not go to

bed at night wishing to dream about the kudos your boss

has given you for going above and beyond your job requirements.

You do those things in New York because there is so much

intense competition; there are real threats in the concrete

jungle and you need to stand out and keep watch to ensure

that no lions come into your camp at night. When you

overcome that sense of fear and actually get to know

your colleagues, not just for the reports they produce,

but for the interests you share and support you give

one another, your work environment takes

on another light.

What took me some time to realize

in France is that it is fine to do what’s necessary at

the office, but then go home and live, not just un

petit peu (a

little bit), but beaucoup (a lot). The French

work to live — by earning enough to take their

once-in-a-lifetime vacations each and every year, even

if that means they save every centime by cutting

back. Many will spend 25 days in Tahiti, where they will

snorkel a minimum of 12 times, and may come back with

a tribal tattoo.

Working Hard, Living Slow in

France

In France, when you arrive in the

morning you actually dive right into your day,

work like mad without a second to spare for a glance

at your phone or the news online, and pack up at 5 p.m.,

quite satisfied and with nothing to prove. In the middle

of the workday, you pause for a long lunch. Sometimes

those long lunches are around tiny tables with

colleagues where you order a menthe à l’eau (mint-flavored

water) as an apéritif, followed by three courses

and a café. I am lucky to share offices with

my husband, and that our apartment is a pleasant 4-minute

walk away. We are able to walk back to chez

nous (our place) to make a sandwich and sit in our

garden on a sunny day. In France, we can exhale and have

daily periods where we reconnect with our lives. We do

not remain completely and perpetually connected to our

professional lives. Where our first lunches in France

were eaten in haste, today I have learned to cherish

time slowed down.

|

| Pausing for a long déjeuner is normale. |

Taking a long déjeuner is

not only totally accepted, but encouraged. A French child

rarely goes to school with a box of processed

foods or a bag of snacks. Children will often actually

return home, on their trotinettes (scooters),

to share a real meal with their family, since meals are

a sacred moment in the day. Perhaps you sit on a park

bench, or go to a local tearoom; even the most basic

moments in daily life are a way to step away and breathe.

Delis exist but are more rare than in New York City,

for example, and should you opt for something preparé,

the boulangerie will

delicately wrap your baguette sandwiche, as

well as a chocolate treat or pâtisserie (pastry),

with a pretty bow. And during

a lazy Sunday afternoon, you can serve poulet rôti (roasted

chicken) with some grainy mustard on pretty china and voila, you

instantly have an elaborate 3-hour picnic luncheon.

At the end of our workday, we meander

around the town center and spend just as much time filling

a small shopping bag as we would a large cart in the

U.S. However, instead of aimlessly perusing aisles full

of unnecessary marketing campaigns or hopping around

for the best prices, we are at a food source, hearing

tales from the fromager about where our cheese was

produced, or the boucher carefully preparing

meat while detailing his favorite recipe. We buy a dozen

oranges to squeeze our own juice, choosing the experience

and taste versus the convenient alternative. We may not

have as great a quantity of merchandise to show for the

shopping trip, but we gain so much more in quality by

slowing our pace and opening our senses.

|

| Going to the market in France

is a sensory experience not to be missed. |

Making Friends in France

Making friends was particularly difficult

as a foreigner at the start of my French adventure. I

was told early on that Americans were “superficial,”

which is fair enough as some Americans think that French

are “snobby,” but was still a little offended by this

notion. My best attempts at conversation did not get

much response. No one really contributed to the conversation,

nor did my French acquaintances open up much other than

to speak about generic subjects. In my experience in

the U.S., we would have been best friends after sharing

the type of conversations I attempted to initiate. We

may have even shared our entire life stories and finished

with a hug.

Over time, I learned that the French

are very selective about whom they allow as a friend,

and that friendship does not come in as many forms as

in the U.S. In France, you have fewer acquaintances or

friends. You socialize and take the time to develop genuine

and deep friendships, such that when they bloom, they

last a lifetime. Less superficial, perhaps. Once

I started nurturing relationships and investing in them,

by having rendezvous over

tea, for example, more French women actually opened

up and reciprocated. When I have a birthday at work now,

I not only receive many homemade cakes, but bisous (kisses)

throughout the day from people who are genuinely happy

to have something to celebrate. When getting to know

someone in France you generally do not just grab a drink

together at the bar on the way to another bar to meet

another friend, but actually invite them to your

home. You then will often host, invite them to your

dinner table, and converse for hours about previous,

upcoming, and dream vacations over a bottle of Bourgogne wine,

along with homemade moelleux au chocolat. The

friends I have made in this way remain, and it is a testament

to how I prefer to build relationships going forward.

The adventure of such a new life,

where you learn to slow down and

focus on a connection with the people around you, often

helps reorient your compass based upon personal and not

just professional values. Having

experienced such immersion, I have become a global citizen

who sees the world differently, who appreciates long

walks and longer lunches, who tries to connect with people

in a deeper manner, while not just interacting with projected

personas. I hope to have many cups of tea with

new friends, or impromptu glasses of bubbly while shopping

in the grands magasins, pauses in a park with

a box of macrons for no good reason at all…

because savoring every little moment, c’est la vie!

Katie Hunter is

a New Yorker who grew up in a haunted house in the "upstate" countryside

who hopped the pond with her French-American husband

in 2009 to live 20 km (12 miles) west of Paris where

she learned the language from scratch. She has since

traveled to 25+ countries, transforming her into a

true global citizen thanks to the multitude of faces,

colors, sites, smells, sounds, tastes and interactions

that she has lived and cherished. She likes to think

outside of the box and travel in the same spirit,

as many trips have been off the beaten path, connecting

with the local communities in a sustainable way.

|