Rolf Potts on Long-Term Travel

Transitions Abroad Founder Dr. Clay A. Hubbs Interviews Rolf Potts

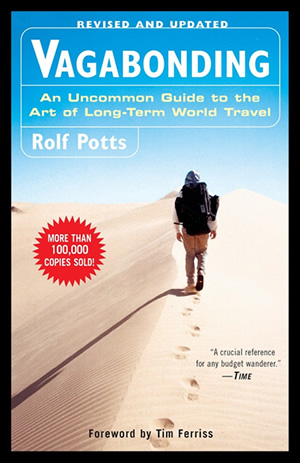

Vagabonding:

An Uncommon Guide to Long-Term Travel (Villard, a

division of Random House) is a remarkably well-written

book in which the author expands on virtually all the

views I have presented in Transitions Abroad over

the past 27 years. Like us, he keeps all his selected

resources — on international employment, volunteer and

short-term jobs, senior and family travel, travel health,

socially and environmentally responsible travel, and

best travel portals — up to date on his website, vagabonding.net,

for all to use. Rolf funded his earliest vagabonding

as an ESL teacher in Korea for two years. He now writes

on independent travel for National

Geographic Adventure and has been called "the

Jack Kerouac of the Internet Age" for his award-winning

dispatches in www.Salon.com. His travel essays have appeared

in National

Geographic Traveler, Best American Travel Writing, and

on National Public Radio.

We caught up with Rolf "virtually" as he was making his way through Central and South America while writing a series of articles on his

travels. Rolf participated in the drive around the world to raise funds which aim to help cure Parkinson's disease. |

Transitions Abroad: Apart

from your views on travel (Example: "Vagabonding is an attitude

— a friendly interest in people, places, and things that makes

a person an explorer in the truest, most vivid sense of the word"),

and your outstanding selection of resources, what I enjoy most

about your book, Vagabonding:

An Uncommon Guide to Long-Term Travel, are the profiles of

earlier vagabonders like Walt Whitman, Henry David Thoreau, John

Muir, Ed Buryn (an early contributor to Transitions Abroad), and

pioneering women vagabonders. Can you give us your own brief profile

of Rolf Potts and explain how a talented travel writer decided

to veer away from the lucrative center of the packaged travel industry

to the independent alternative?

Rolf Potts: Like many people who started traveling at a rather young age, my initial attraction to independent travel was that it was cheap. I could simply get more travel from my meager funds by seeking out my own

routes, restaurants, attractions, activities, and hotels. In time, I realized that this was the best way to immerse yourself in local cultures — even if you do have more money to spend. So I never got involved in the packaged travel industry

because I was never a packaged traveler.

I have always been interested in travel. When I was a kid growing up in Kansas, I would always measure the calendar year by when we would leave on family trips to Colorado or Missouri. By the time I was in college in Oregon

I was taking summer road trips on my own and jumping freight trains around the Pacific Northwest. When I finished college I knew I didn't want to go straight into the professional world, so I worked as a landscaper for 8 months and saved the

money for a trip around North America. A friend and I converted a 1985 Volkswagen Vanagon so we could sleep inside, and we hit 38 states in eight months. We hiked the Grand Canyon, rode with a police patrol in Houston, hit Mardi Gras in New Orleans,

spent an entire month in Florida during spring break season, went rock climbing and rafting in North Carolina, slept in monasteries and hostels and public parks — and that was just the first few months. It was my first long-term travel experience,

and it was really addictive. I've lived and traveled overseas for over seven years now (first as an English teacher in Korea, and later as a travel writer), but I still love to go back and travel America.

As a writer, my first break came in 1998, when my travel story about Las Vegas appeared in Salon.com. Seeing my name in print was addictive, and by the end of the year I'd written five more stories for Salon. But the real

break came in 1999, when I wrote a story called "Storming 'The Beach'" (a gonzo piece about the filming of a Leonardo DiCaprio movie in Thailand), which appeared as a Salon cover story. By that time I was traveling full-time on money

I'd earned as an English teacher in Korea, so Salon offered me a gig as biweekly travel columnist. It was a nice arrangement: I gave them inexpensive content, and they gave me great exposure. The column really raised my profile and allowed me

to move on to print magazines and books. But of course none of this success would have been possible without four years of writing failure leading up to 1998. Earlier, starting in 1994, I had tried to write a book about my USA travels, but after

years of toil, agents and publishers simply weren't interested. It was a frustrating experience, but I learned some important lessons and I began to find my narrative voice. My first published travel story — the Las Vegas piece in Salon — started

out as a chapter of that failed book. I've been a full-time writer for five years now.

Transitions Abroad: You write that vagabonding is "an attitude . . . an uncommon way of looking at life." Assuming that most of us have such an attitude, how can we afford the time and money to act on it?

Rolf Potts: Part of one's vagabonding attitude is realizing that the only true wealth you have in life is your time — and how you spend that time is more important in life than how you spend other types of wealth,

such as money. Thus, if you simplify your life in such a way that you are buying less "things", you will soon find that you have bought yourself a wealth of time.

This isn't always something that happens overnight. The vagabonding urge is something that some people have to cultivate over many years. It may take, say, five years before you are able to create the time and save up the

money for a meaningful long-term travel experience. But, as I say in my book, that preparation is part of the journey. When I was working as a landscaper in Seattle before my first trip around the U.S. ten years ago, I can’t overemphasize

how much energy I got from thinking about what was going to happen to me six months, five months, four months down the line. I was mowing lawns, and it was very physical work. It was raining all the time, but I was so happy because that labor

was earning me my freedom. So work is very important in preparing for travel; you just have to make your work serve your interests instead of the other way around.

Transitions Abroad: We know that most Americans seldom go abroad for anything other than short vacation escapes or business trips. Is that because they are not interested in learning about the rest of the world? If

so, do you think the events of 9/11/01 changed that significantly?

Rolf Potts: One of the reasons so few Americans travel for long periods overseas is that America is a huge and diverse country. When I went on my first vagabonding journey in 1994, I didn't even own a passport. I traveled

for eight months across North America during that trip, and I could have traveled for eight years without losing interest or seeing the same thing twice. So I'd say part of the overseas travel issue is that America itself offers so many travel

options.

But there is a deeper issue at hand. Between our frontier history and our current superpower status, we Americans tend to be inward-looking. We're an immigrant culture, and part of the immigrant ideal is tied to the idea

that we (or, rather, our ancestors) all chose to leave the old world behind and live here. It's a weird idea, really. As an immigrant culture, you'd think Americans would be more rootless, more given to wandering overseas. But it seems like we

mainly express our rootlessness by moving around within the United States. California — with its fast-food, optimism, and vacuous pop-culture — is the typical metaphor for American rootlessness. Walt Whitman or John Muir or Jack Kerouac gave

us a countercultural vision of rootlessness — one that is very much respected, but rarely put into actual practice.

I think most Americans will always be captive to the American Dream, and that means most Americans will stay home, work hard, keep up with the Joneses, and obsess over the newest things. They won't allow time for long-term

travel, and in many cases that's fine; I don't think that everyone feels the calling to go vagabonding. But the fact is that hard work and keeping up with the Joneses don't always make a person happy or allow for a full life — and there is a

time-honored (and romanticized) American counterculture tradition that encourages individuals to strike off for themselves and discover the world.

By using the word "counterculture," of course, I am inviting misinterpretation, since these days that word implies a fashion statement rather than a life-choice. Since the sixties or so, "counterculture" has

been institutionalized into a consumer notion that vaguely involves sex, drugs and rock-and-roll. That's all good fun, but it's a very limiting notion that throws you back to the rigid clique-structure of high school. After all, few of America's

counterculture icons lived up to the bohemian stereotype. Thoreau was a philosophical radical, but he was very much a prude in day-to-day life. Kerouac is often regarded as a marginal character, but he was an Ivy League jock and a devout Catholic.

What set these men apart was not fashion or stereotype, but the individual choices that dictated the way they lived.

So I think long-term travel — and true countercultural living in general — will always be a private and personal choice, especially in America. Some people will feel the calling to see their travel dreams actualized. My

book seeks to encourage and inform people who've felt that persistent itch to get out on the road.

Transitions Abroad: Back to the time and money question: If someone shares our views and loves to vagabond but only has two uninterrupted weeks to do it in, what would you recommend?

Rolf Potts: I would recommend traveling to only one place and trying to experience it was much as possible. One mistake that many people make on short vacations is trying to cram in too many activities — and that means they spend half

of their vacation running around from one place to another. Better to just stay in one place and wander — keep your itinerary open and allow yourself to relax, improvise, and get to know the locals. I can guarantee this will lead to a much more

memorable travel experience than if you had spent that time running around and ticking attractions off a list.

Follow Rolf Potts via Twitter, Facebook, or his website full of resources, articles, and travel writer interviews, his personal blog, a collaborative blog, and much more..

|